Athletes' opportunity to be courageous still resonates in Mexico City

Fifty years have passed since John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised their fists against racial discrimination in America. Athletes continue to stand up — or kneel — to shed more light on social injustices, even if it costs them their livelihoods.

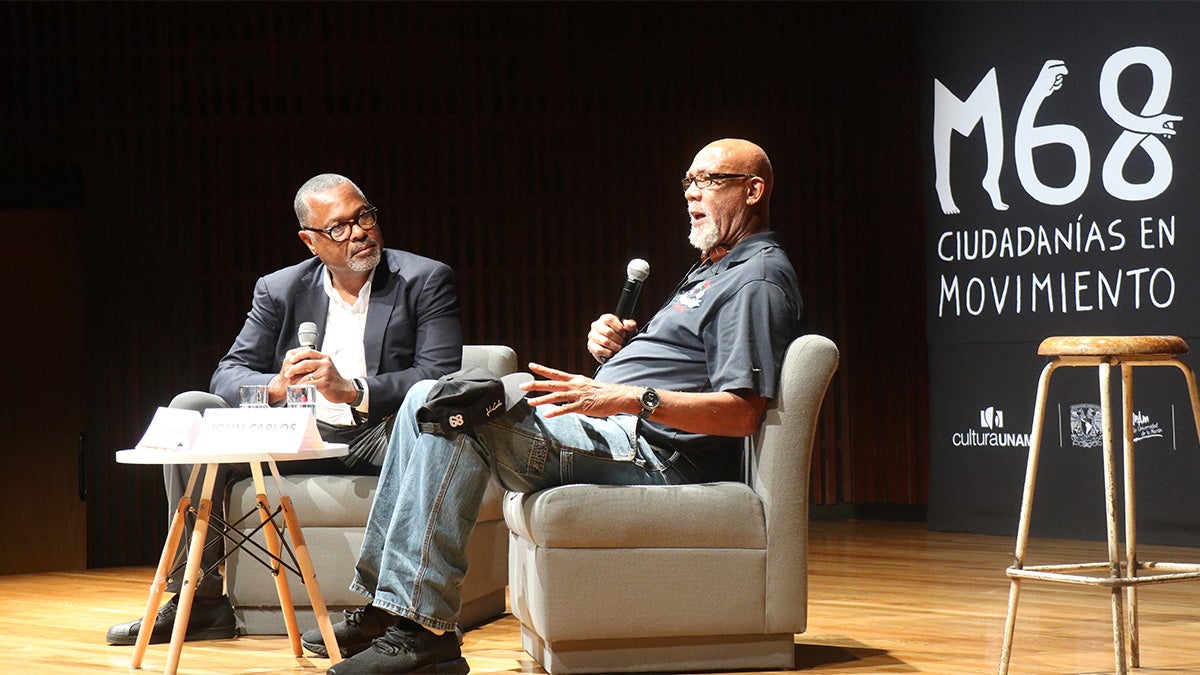

On Sept. 24, Carlos, gold medalist Wyomia Tyus and former Minnesota Viking punter Chris Kluwe joined Kenneth Shropshire of the Global Sport Institute and Mexican journalist Juan Villoro to talk about athlete activism during the 1968 Summer Games and how, 50 years later, some of the same issues parallel today’s protests.

“We all, sooner or later, have the opportunity to be courageous,” Shropshire said at the event at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Carlos used his opportunity on the medals podium to raise his fist for something that was far more valuable than the medal around his neck: civil rights and equality. Even though he was only 23 at the time, Carlos explained how, as a child, he knew there was going to be a moment when he would represent something bigger than anything he could imagine.

Carlos told Shropshire that: “God gave me a vision: He showed me myself standing on a box in a field. I could hear people applauding vigorously. As a kid, you want to wave because you want to be seen, and I got my hand up to how you see me in the portrait and was frozen in time.”

But the day on which he fulfilled that vision on the medals podium in Estadio Olímpico Universitario in Mexico City in 1968 did not end the way he foresaw.

“The people started applauding vigorously, and then all of a sudden decided they didn’t like what they were seeing and they turned into venom and anger,” Carlos said. “I left the victory stand that day with the thought in mind that I was born June 5, 1945 to be in Mexico City in 1968. That was my calling in life.”

However, great moments can come with great pain. Carlos said when he returned to the U.S. afterward, he was treated like a “cursed individual.” Carlos explained “people had love, admiration and respect for (me) before going to Mexico City, but when I got home all that love and admiration was gone.”

He told Shropshire and the audience that the price for his action was difficulty obtaining employment, his children and family were ostracized and the suicide of his wife due to the negative backlash. But nothing Carlos did while on the podium was for him. He wanted not only a better world for himself, but also for his children and all people. He wanted to pave a path for others to stand up and make the world change for the greater good.

“We three cannot change society to make it better without you,” Carlos said of himself, Tyus and Kluwe, who shared the stage. “The change you’re making is not for yourself; the change you’re making is for your kids.”

Tyus was the first person, male or female, to win the 100-meter dash in consecutive Olympics, first in 1964 Summer Games in Tokyo and then in 1968.

For Tyus, who had not visited Estadio Olímpico since completing 50 years ago, “when we started walking into the stadium, I started getting chill-bumps,” she said. “The whole excitement of being here and remembering all the good things that happened. Today is a day that will be etched into my memory until I’m gone.”

Growing up in the segregated south, she explained she had few rights. “I was at a stage in my life where I was always fighting for civil rights,” Tyus said of the period when the Mexico City Games took place.

She told a story from her childhood of a Christmas when her parents wanted to give her a cowgirl costume. However, the 6-year-old Tyus demanded to wear a cowboy outfit instead. Her parents told her she should follow her mind and believe in what she thought was right. Leading up to 1968, “here was so much unrest going on in the world that we all had to pay attention to it, and the only way to help people — if it’s by speaking out or something — you should do it.” Tyus said. “We had a platform where that could happen and the world could see, and the world needed to know.”

Tyus, a tennis fan, recalled that growing up, girls were not allowed to play with boys, not expected to engage in sports and not given a level playing field.

Of Serena Williams’ experience at the U.S. Open, “I felt that in that moment there, [the umpire] felt like he had no choice to do what he did. But he did have a choice, all [Serena] was saying is she wanted an equal playing field,” Tyus said. “We need strong women like that. Black women are not supposed to be that strong when talking about issues, but we are.”

Tyus drew similarities between how in 1968 women had very little to no fairness when compared to men, and, although the situation has improved over time, how there is still a long way to go. Tyus believes women such as Serena can blaze a trail for more women to follow.

After Tyus and Shropshire finished their segment, Mexican journalist Juan Villoro led a panel that included Carlos, Tyus and Chris Kluwe, a former NFL player cut from the Minnesota Vikings after he expressed support for same-sex marriage.

Kluwe declared: “Sports is politics. You can’t keep politics out of sports. The society we live in is discriminatory and oppressive, and as someone with a platform and who, as an athlete, was taught to lead and do the right thing. It is incumbent on us to make the world a better place.”

Kluwe spoke about how athletes put in so much work and dedication to not only to play a sport, but also be among the best in the world at it. “To be discriminated against because you’re trying to raise awareness of what is a serious problem. It goes to show that in America we have so much work to do,” Kluwe said.

“In terms of dealing with civil rights, a snail has moved farther in that 50 years than we have moved relative to us fighting for civil rights.” Carlos said.

Although cynical, Carlos said he believes that his actions are starting to come full circle as the push for racial equality has become prevalent in today’s society. Carlos, Tyus and Kluwe have taken a stand and hope to pass the torch to a younger generation to use their voice to speak out on injustices in our world, even if it means taking a risk.

“I definitely think it can change,” Tyus said. “We all have to have values, we all have to believe in something, we also have to look around us and see what’s happening to see if this is how we should live as human beings.”

Tyler Dare is a senior journalism student at Arizona State University