Brutality of relegation one of the great dramas of Premier League

Editor's note: Since publication of this column on May 11, Swansea has indeed been relegated.

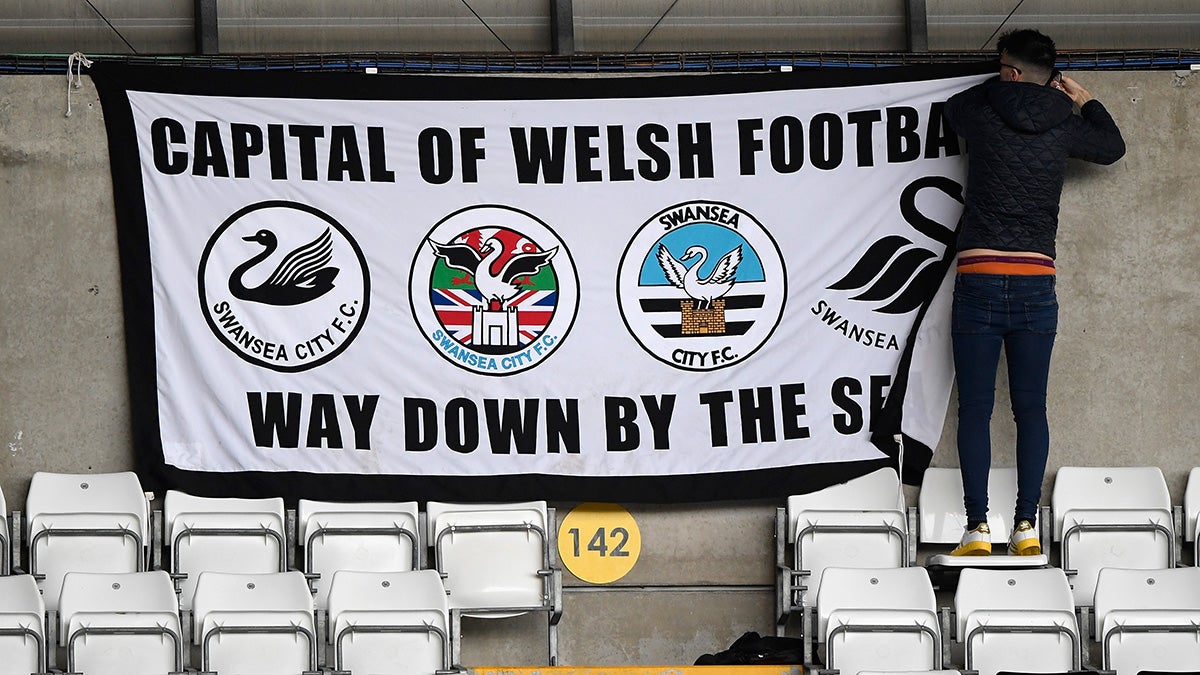

The mood in Swansea is grim these days. The Welsh seaside city’s beloved “Swans” are facing the increasingly likely prospect of relegation from the English Premier League. As if to compound the misery, Swansea City’s descent, if it is confirmed this coming Sunday — the final day of the season — will coincide with the promotion of its fierce rival, Cardiff City, which has secured a place in the Premier League next season.

The drama posed by relegation in Europe’s football leagues is unimaginable to most American sports fans. In the NFL and NBA, teams that finish last receive tender, parity-inducing care and attention in the form of top picks in the college draft, easier schedules, and so on.

Mark Cuban was roundly admonished last year when he admitted that once they were out of the playoffs, his Dallas Mavericks pretty much did everything possible to lose games late in the season. His candor was shocking, but he was only expressing what a lot of fans and teams think privately in leagues with perverse incentives to lose.

Judging by their respective sports cultures, you’d think the United States is the socialist country obsessed with equality and social welfare for all, and Europe the land of heartless sink-or-swim, survival-of-the-fittest capitalism.

In the Premier League, three teams are relegated to the second division (“the Championship” of the English Football League) at the end of every season, and three come up. Indeed, these promotions and relegations take place up and down the entire pyramid of English football divisions. The stakes are huge. Promoted teams feel like they have won the lottery. Those dropping out of the Premier League must prepare to say goodbye to more than $100 million in TV revenue a year, not to mention global exposure. Swansea has a second-city inferiority complex to Cardiff, the capital and largest city of Wales, only about 40 miles away. But in recent years, Swansea fans could feel proud that it was their team, and their city, that was being followed across the world, not Cardiff.

If the NFL had such a Darwinian system of relegating the bottom teams to some lesser division, over the past three years fans of the Texans, Colts, 49ers, Bears, Jaguars, Titans, and Chargers would have had to bid farewell to the big time for at least a season. It’s a preposterous idea, of course, until you realize that the Cleveland Browns would have been on that list every one of those seasons, as if making a principled case for relegation.

[beauty_quote quote='“It’s like you’ve married a woman who sings part-time in the pub and then suddenly and for no apparent reason, she’s awarded a massive record deal. Some of the glory reflects on you, sure, but then you realize she’s no longer the woman you married.” - Martin Johnes ']

Relegated teams in England are given “parachute” payments to soften the blow, but some are not seen again in the top flight for a long time, if ever, while some bounce right back. Sunderland, one of the three Premier clubs relegated last season has repeated the feat this year, relegated from the second to the third division.

Of the 20 current Premier League clubs, only six – Arsenal, Chelsea, Manchester United, Liverpool, Tottenham, and Everton – have been in the top flight every season since the league kicked off in 1992. So the remaining 14 clubs – make that 13 given that Manchester City has since been acquired by Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi – appreciate the impermanence of belonging to one of the world’s most storied leagues. Indeed, just in this 2017-2018 season, eleven teams have been in the drop zone (bottom three slots) at one point or another. That means a majority of clubs, and their fans, spend much of their time worrying about their survival. A total of 49 clubs have played in the Premier League, another testament to its remarkable churn over a quarter-century.

Chris Pearlman, the American chief operating officer of Swansea, told me in his office a couple of weeks ago that he and the club’s American owners appreciate that relegation and promotion are integral to the game, and part of what makes English soccer so exciting. English pundits love to joke that wealthy foreigners have rushed in to snatch up their football clubs without realizing (until it’s too late) they can be relegated, but Pearlman notes that the risk is baked into the price of the smaller clubs, that Swansea would be worth far more if it weren’t for relegation.

Still, it’s a brutal prospect. “It’s one thing to understand the idea of relegation as an intellectual matter, and appreciate its drama from afar – it’s quite another thing to live through it.”

“This club means everything to this community,” he added, “which makes it very difficult.” Accentuating Swansea City’s deep community roots, Swansea is the only Premier League club partly owned by the supporters’ trust, and the club gets many accolades for subsidizing tickets for their fans to attend away games.

The dire-straits sentiment was echoed by the cab driver who took me to Liberty Stadium the next day for the Swans’ ill-fated encounter against visiting Chelsea. “Mostly what we have here in Swansea is this club and the university,” he said. He fears that he and everyone else working in tourism would take a severe hit with relegation.

Martin Johnes, a historian at Swansea University who focuses on Welsh national identity and sports, takes a more sanguine view. He says no one expected the club to remain in the Premier League for seven seasons after being promoted in 2011.

“To be honest, the novelty and excitement that you’re suddenly watching the Manchesters and Liverpools come to town wears off, and over time it becomes a joyless grind to stay up,” he said. Long gone are the days when the club’s fearlessly creative style of play earned them the nickname of Swanselona, a play on Barcelona. Johnes admitted the branding of the Premier League is such that there are now millions of people around the world aware that there is a place called Swansea with a Liberty Stadium (named after an insurance company, truth be told) who would otherwise not know there is a Swansea. He’s just not sure it makes all that much difference in the end.

Johnes has been attending Swansea matches since he was 10, back in 1983, when the club played in old Vetch field, its home from 1912 to 2005. In his years as a fan, Johnes has followed the club in four different divisions. He also helped me grasp (in reaction to my perplexed “why do they all play at the same time?”) that proper fandom means obsessing only over the division your team is in; this isn’t like having a college team on Saturdays and an NFL team for Sundays.

“You can’t support a team in one division just because your team is in another division, because then what happens the year one of them is promoted or relegated and they are competing against each other?” Johnes asks.

When your small club does make its way up to the Premier, and is not accustomed to it, it’s a bit of an adjustment for fans.

“It’s like you’ve married a woman who sings part-time in the pub,” he explained, “and then suddenly and for no apparent reason, she’s awarded a massive record deal. Some of the glory reflects on you, sure, but then you realize she’s no longer the woman you married.”

Still, judging by the grim mood, the frustration aimed at the coach, the players, the current American owners, and the former owners, most Swansea fans don’t share Professor Johnes’ fatalism. Call it short memory or ingratitude, but they had grown accustomed to their Premier status, and don’t want to lose it. They don’t want to go back to being wed to a part-time pub singer, beyond the spotlight trained on Cardiff.

I feel for them, but also, as an American sports fan, I can’t help but envy the drama of it all. And, of course, I can’t help but think of Cleveland, and its Browns. If only.

Andrés Martinez is a professor of practice in the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

Related Articles

Opinion: Proposed Wembley sale latest move in globalization of Premier League

Wembley: Shahid Khan wants to host World Cup and Super Bowl at stadium

Don't count on a boycott to interrupt Russia World Cup

Fielding diverse lineups, ownership pays off in Premier League, Major League Baseball

England’s Premier League is globalized, but even Brexit-rattled Britain cheers. For now