Athlete activism is on the rise, but so is the backlash

On May 23, 2018 the NFL announced a new policy that requires players and league personnel on the field to stand for the national anthem, but gives them the option to remain in the locker room if they don't want to stand. Teams will have the power to set their own policies to ensure the anthem is being respected during any on-field action. If a player chooses to protest on the sideline, the NFL will fine the player. Earlier this year, GlobalSport Matters looked at why reaction to player protests is so strong.

In March, the Charles Barkley who hosted Saturday Night Live was a faint image of the Charles Barkley who spoke out on political issues in the early ‘90s. The current Barkley is a cuddly class clown who is, not coincidentally, much more beloved than when, as an NBA all-star 25 years ago, he’d hold court on political matters in the locker room of the Philadelphia 76ers.

“Just because you give Charles Barkley a lot of money, it doesn’t mean I’m not going to voice my opinions,” he lectured the media throng around him back then. “Me getting 20 rebounds ain’t important. We’ve got people homeless on our streets and the media is crowding around my locker. It’s ludicrous.”

At the time, his friend and rival, Michael Jordan, explained his unwillingness to endorse a credible black challenger to right-wing Senator Jesse Helms in his home state of North Carolina by saying “Republicans buy sneakers, too.” Barkley’s response was to pose on the cover of the hip-hop basketball magazine SLAM with Spike Lee, proclaiming themselves to be “Nineties Niggas.” “I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” Barkley said to the sportswriters chronicling him, echoing a Muhammad Ali line from the ‘60s.

Now here he was on the set of SNL, just a few months after stumping for Democrat Doug Jones’ Senate election in his native state of Alabama, (“at some point, we gotta stop looking like idiots to the nation”) and just days after Fox News’ Laura Ingraham had told LeBron James to “shut up and dribble” after he’d deigned to talk about social justice. “A lot of athletes are worried that speaking out might hurt their career,” Barkley said in his SNL monologue. “Well, here’s something that contradicts all of that: Me. I’ve been saying whatever the hell I want for over 30 years and I’m doing great…LeBron, keep on dribbling and don’t ever shut up.”

The audience cheered. And therein lies the difference in athlete activism today. Athletes have always spoken out on societal issues—Ali’s anti-Vietnam stand in the ‘60s is oft-mentioned, but you could go all the way back to Irish long-jumper Peter O’Connor, an activist for Ireland’s independence, waving the Irish flag when the British anthem played during the medal ceremony at the 1906 Olympic games. But few cheered. Ali, in fact, wasn’t widely beloved in opinion polls until—not coincidentally—Parkinson’s disease had robbed him of his voice.

“There have always been instances of social protest by athletes,” says Dr. Douglas Hartmann, chair of the sociology department at the University of Minnesota and author Midnight Basketball: Race, Sports and Neoliberal Social Policy. “But now it’s a movement, and it’s not just professional athletes.”

Since at least 2012, it’s become hard to pick up a sports page and not read about an athlete taking action or weighing in on life beyond his or her field of play. Name the issue and there’s been an athlete, or group of athletes, engaging it: Racism, police brutality, gay and transgender rights. Others—Bob Knight, Curt Schilling—have stood for conservative causes.

What was once verboten has become trendy, and that’s brought along its own backlash, as the NFL has found out. Last season, league TV ratings were down 10 percent and at least one study found that nearly one-third of 1,000 random respondents said they were less likely to watch a game because of players protesting during the national anthem. But that hasn’t slowed the parade of athletes who are wading into societal matters.

What explains the trend? “It’s a lot easier to feel free enough to get involved and take stands when the greatest athlete in the world leads the way,” said Los Angeles Ram Connor Barwin, whose foundation rebuilds inner-city parks and who has supported political candidates, of LeBron James. James, who, in addition to dust-ups like the one with Ingraham, has underwritten some $40 million in college tuition for underprivileged children in his hometown of Akron, Ohio.

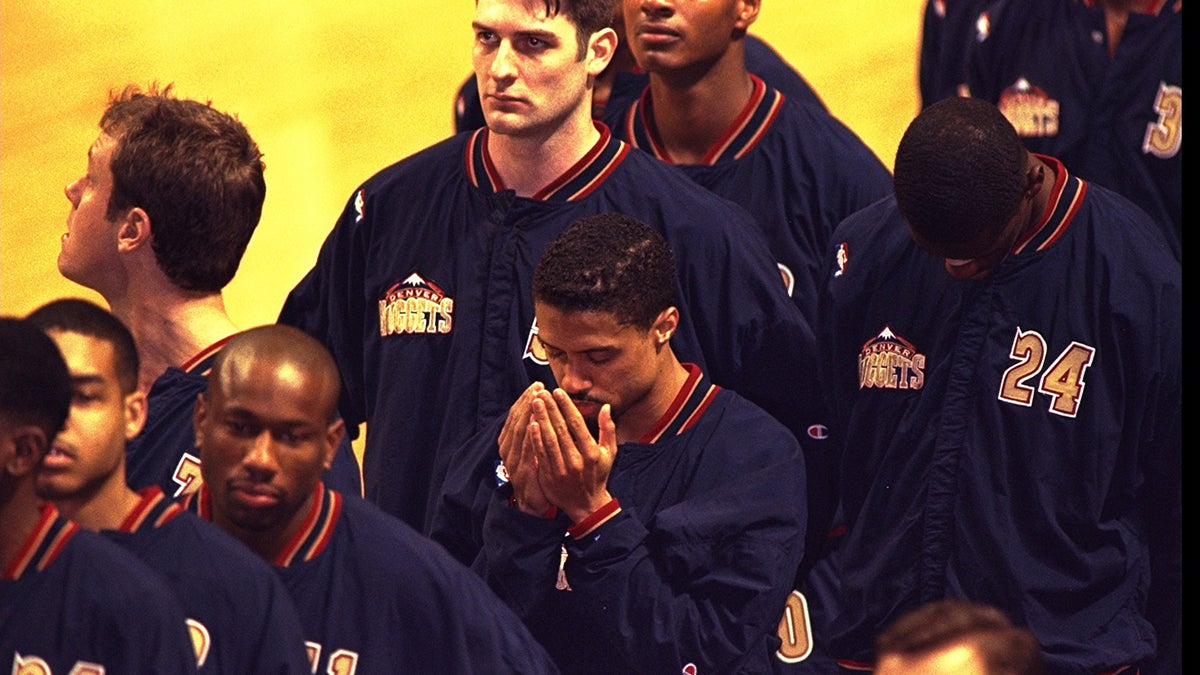

In the past, athletes like Ali who took socially impactful stands were isolated and shunned. Barkley says his outspokenness in the prime of his career cost him $10 million in endorsements and subject him to criticism from the front office of his team, his league and the media. Controversial stands taken by NBA players Craig Hodges and Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf—whose protest over the national anthem presaged Colin Kaepernick’s—resulted in the end of their careers, respectively. When Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists during the medal ceremony in a Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics, Brent Musburger referred to them on-air as “black-skinned stormtroopers” to nary a complaint.

What’s changed? In recent years, Kaepernick’s blackballing notwithstanding, establishment forces—perhaps kicking and screaming—have come to endorse, or at least grin and bear, athlete activism. Last fall, team owners lined up with NFL players taking a knee, defying President Trump; in response to campus racism, a boycott on football activities by the University of Missouri football team, supported by its coach, forced the resignation of the school’s president; and the Miami Heat organization stood by James and his then-teammates when they tweeted a photo of themselves wearing hoodies with the hashtag #WeAreTrayvonMartin.

Establishment forces like teams, leagues and mass media outlets have come to realize the power and popularity of today’s athletes and, perhaps calculatingly, have come to be on board with athletes who flex their social justice muscle. Ironically, the backlash now increasingly comes from the anti-establishment, nativist fringe.

“Don’t underestimate the Trump effect,” says Hartmann. “In the past, presidents have used sports to unify the country. When, last fall, Trump attacked primarily African-American football players who were protesting police brutality, he used politically motivated, racially coded speech to mobilize a nativist, reactionary response.”

In that sense, Hartmann says, unlike in past examples of athlete protest, in this case the athletes were responding to, rather than making, a provocative message. Which gets us to that other hulking linebacker in the room: Race.

“There is and has always been a societal backlash against athletes, particularly Black athletes, who speak out against injustice,” says Dr. Peter Kaufman, professor of sociology at the State University of New York at New Paltz, and author of Boos, Bans, and Other Backlash: The Consequences of Being An Activist Athlete. “As William Rhoden wrote in his aptly titled book, many people view, although they would never admit or be even be conscious of, Black athletes as 40 Million Dollar Slaves. Just shut up and play, entertain us. That’s what we pay you for.”

That’s the resentment the likes of Trump and Ingraham have instinctively sought to exploit for political purposes. The same bitterness exists for celebrities as a whole who speak out, but it’s easier to mobilize it by using African-American athletes. “First, there’s long been this ideology of sport as apolitical,” says Hartmann. “The separation of sports and politics has long been enshrined in Olympic ceremony and protocol, and a different standard has applied to, say, actors and actresses. So athletes who speak out have been up against that norm. But when Laura Ingraham calls LeBron’s comments ‘ungrammatical’ she’s also playing off dumb jock stereotypes unique to the athlete, especially the African-American.”

But what the opponents haven’t counted on is the media savviness of today’s athlete. In the past, activists like Ali and Jim Brown were not only dependent on the often skewed filter of sportswriters, who were themselves saddled with biases, but also on a comparatively slow news cycle. Ali, for example, might be called a “draft dodger” and the defamatory claim would have the airwaves and newspaper pages to itself for days. Today, James and his colleagues are able to respond in real time to their critics, often capturing the high ground right away.

“For better or worse, social media has changed the landscape, particularly when it comes to social justice movements,” says Kaufman. “Studies have shown that the World Trade Organization protests in Seattle in 1999 were driven by social media in a game-changing way. Fast forward to today, when our lives are structured around hashtags and soundbites. Social media has been a powerful tool to bring about solidarity, so an athlete who speaks out never has to really be all alone out there.”

U bum @StephenCurry30 already said he ain't going! So therefore ain't no invite. Going to White House was a great honor until you showed up!

— LeBron James (@KingJames) September 23, 2017

So there was James last fall, stealing the headline from Trump, the master headline maker, after the president preemptively withdrew a White House invitation to the NBA champion Golden State Warriors after that team’s star, Steph Curry, expressed his desire to skip the traditional visit. “U bum,” James tweeted. “@StephenCurry30 already said he ain’t going! So therefore ain’t no invite. Going to White House was a great honor until you showed up!” The flurry of Twitter support for Curry, led by James, bore out Kaufman’s point: The protester no longer has to go it alone. And it showed that athletes—with their millions of followers—could own the public narrative instead of finding themselves at its mercy.

It’s a power trickling down to athletes who don’t have the freedom that comes with million-dollar contracts. “In recent years, college athletes have publicly taken up the causes of racial justice and student-athlete rights, while still playing,” says Dr. Victoria Jackson, a sports historian at Arizona State University. “They’ve been inspired by role model like LeBron James and Colin Kaepernick.”

Jackson cites jocks turned change agents like Kain Colter, the quarterback who led the ultimately unsuccessful movement to unionize his team; Oklahoma’s Eric Striker, who spoke out when a racist fraternity video came to light on his campus, and who engaged the “shut up and play” backlash in the pages of Sports Illustrated: “As a young man I thought, I’m gonna change the world, but I didn’t know how. Now I have a platform and a voice people want to hear. Why would I stop talking?”; and Nigel Hayes, who, as a University of Wisconsin basketball star, called attention to NCAA exploitation by carrying a sign that read “Broke College Athlete Anything Helps” and who wrote a public letter critiquing his university on race relations: “We shouldn’t be commodified for mere entertainment, but respected as individuals with the ideas and the ability to contribute to society.”

There there are those athletes who will likely never show up on Sportscenter. Hartmann cities the case of Olivia House, a sophomore soccer player at Division III Augsburg University in Minneapolis, who knelt during the anthem before her games last season after seeing Megan Rapinoe of the U.S. women’s national team do the same. “The parents of some of her teammates were upset, and they spoke to their kids, and that led to conversations within families and on the team about real issues,” says Hartmann. “It didn’t change the system, but it created awareness and started a dialogue.”

Which is, after all, what movements do. The more athletes at all levels feel emboldened to make their voices heard on a wide range of issues, the likelier it is that the days of “Republicans buy sneakers, too” will be in our cultural rear view mirror. Some have called that Jordan quote apocryphal, but I asked him in the pages of GQ magazine in 2007 if he regretted it and he said: “No, I privately supported [the challenger to Sen. Jesse Helms] Harvey Gantt…But if you asked me the pros and cons of Harvey Gantt, I’d have been lying to say one thing…I’d only be setting myself up for someone to scrutinize my opinions, which were limited, because I never channeled much energy into it.”

Though he has been pilloried for the comment, in this explanation Jordan makes a compelling point: The call for athletes to speak out just might be a type of media set-up. Which is why today’s generation of athlete activists have taken the work ethic they practiced in their sport and applied it to their activism. Two years ago, Malcolm Jenkins, the All-Pro safety for the Super Bowl champion Philadelphia Eagles was, like Jordan, focused on excelling in his sport. But then he saw the news reports of the killings by police of Philando Castile in Minnesota and Alton Sterling in Louisiana.

“I thought, ‘That could have been me, or my brothers, or my cousins, or one of the kids my foundation serves,’” he says. “I looked at myself in the mirror and asked, am I doing enough?”

So he got to work. He read The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, was transfixed by Ava DuVernay’s 2016 documentary 13th, interviewed inmates and the formerly incarcerated, picked the brains of community leaders, and went on ride-alongs with the police in Philadelphia’s most dangerous neighborhoods. Jenkins decided he wasn't just going to symbolically protest; he was also going to advocate for substantive criminal justice reform.

When, last season, Jenkins’ teammate Chris Long, who is white, put his arm around Jenkins during his raised fist national anthem protest, and when the two lobbied state officials together in support of a Clean Slate Bill that would seal old, non-violent misdemeanor offenses so those re-entering the work force could better find meaningful employment, it sent an important message: “Civil rights and criminal justice reform is not a black or white issue. It’s an American issue,” Jenkins says.

The backlash, Jenkins reports, has been minimal. In part, that’s because he was savvy enough to understand what Jordan was getting at: He made himself an expert on a public policy issue. Of course, winning has also likely contributed to the resonance of his message.

But Jenkins is politically astute enough to know that, when the backlash comes, it’s usually in the form of: You’re a millionaire athlete, what do you have to complain about? Shut up and play! Like so many others of today’s athlete activists, Jenkins flips that script, and argues that to whom much is given, even more is required. We have a patriotic duty to use our platform to better society, he says. And, somewhere up there, Ali is shuffling in celebration.

Larry Platt is the co-founder and editor of The Philadelphia Citizen, a nonprofit solutions-reporting news site, and is co-author of the New York Times bestselling memoir Every Day I Fight, the story of ESPN sportscaster Stuart Scott’s epic battle with cancer. He has written for GQ, the New York Times Magazine, New York, Men’s Journal, Playboy, and Salon.com, among other publications, and can be reached at larryplatt.net

Related Articles

Athlete activism has global, historical aspects

New book draws line from Paul Robeson to today's athlete protests

Opinion: Activist Philadelphia Eagles are on the clock with invitation to White House