Judging apples to apples: Should steroid users be admitted to the Hall of Fame?

The great Willie Mays had to be the one to strike a position regarding the selection of players from Major League Baseball’s so-called steroid era into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, his own godson, in particular.

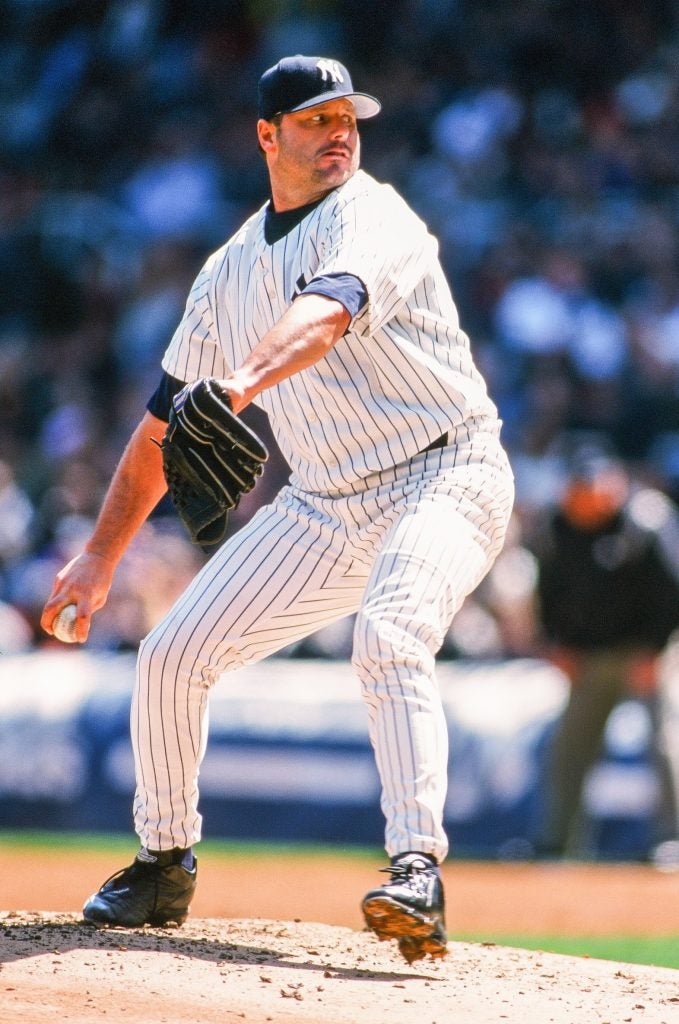

Mays, is the godfather of Barry Bonds, the all-time leader with 762 career homers, including a record 73 in a single season. Bonds, along with 354-game winner Roger Clemens, has been made the poster child for an era when attendance was high, the Bash Brothers ruled and money was rolling in for baseball teams.

The occasion was Aug. 11 at AT&T Park when the San Francisco Giants retired Bonds’ No. 25,11 years after he broke Henry Aaron’s all-time home run record.

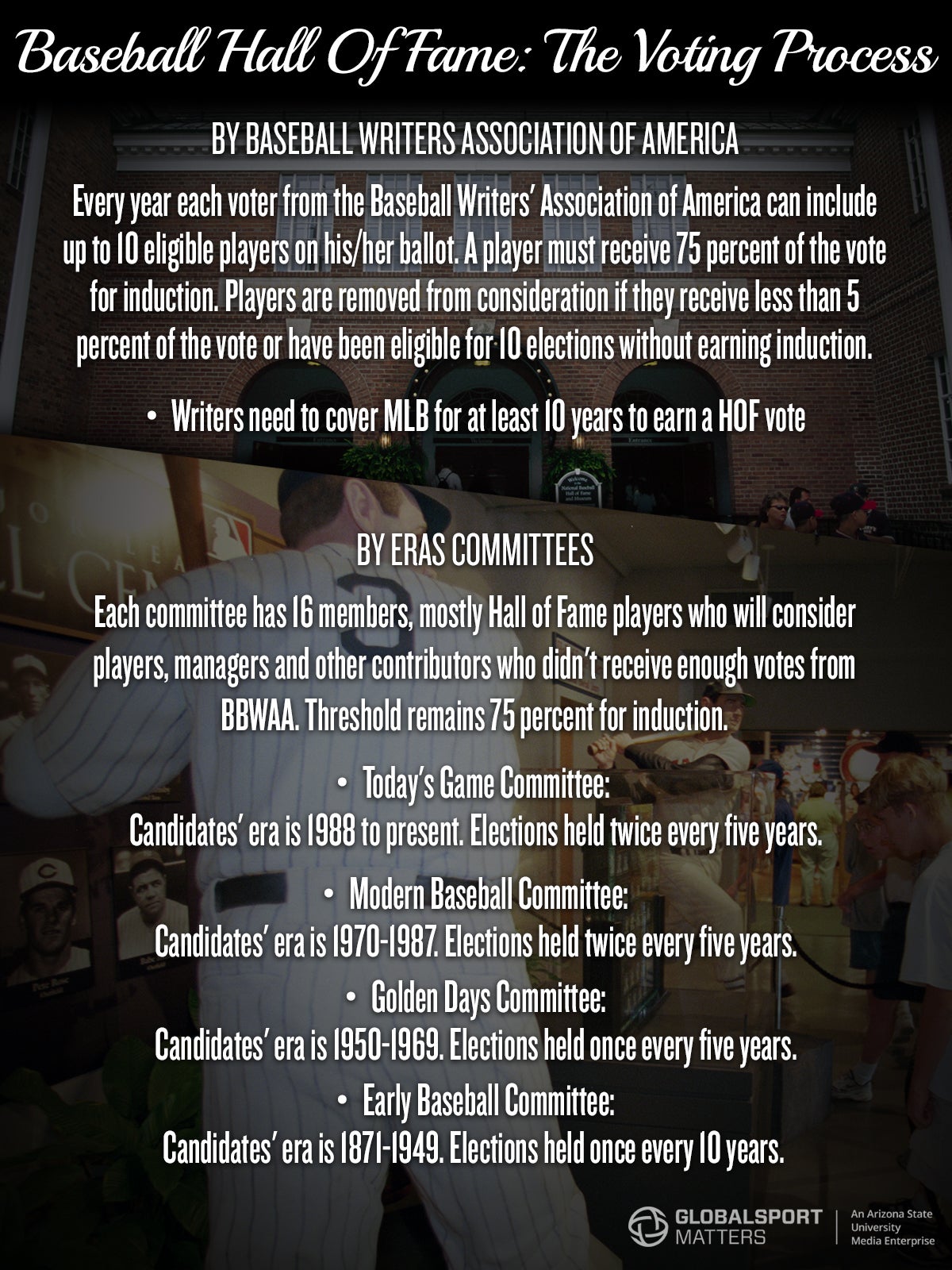

In the ardent hope of Mays, now 87 and mostly blind, perhaps this latest recognition will lead to Bonds’ election to the hallowed Hall by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. Bonds has four years remaining on the writers’ ballot before moving to the 16-member Today’s Game Committee.

With 56.4 percent yes votes this year, he’s 79 votes away from election. To be voted into the Hall, a candidate needs to receive 75 percent of the votes. This year the cutoff was 317 of 422 ballots filed by the BBWAA. A candidate needs at least 12 of the 16 votes on an Era Committee, which is a very tough get, particularly for a player under the shadow of performance-enhancing drug use.

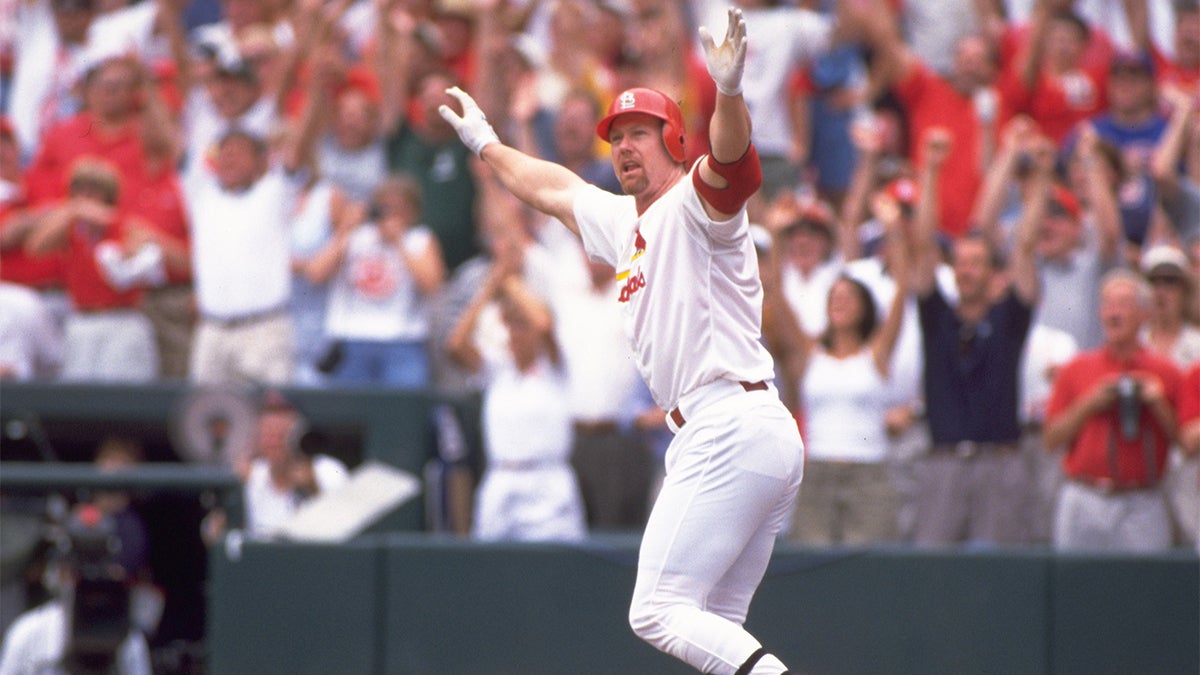

For example, after 15 years of rejection on the BBWAA ballot, Mark McGwire wasn’t given a sniff in 2016 by the Today’s Game Committee, which didn’t vote in any player, but honored former Commissioner Bud Selig and Atlanta Braves president John Schuerholz, whose careers overlapped the tainted era. For Bonds, Clemens and McGwire, the taint of steroid or performance-enhancing drug use are keeping them out of the Hall.

A brief history

In 2002, as Major League Baseball and the MLB Players Association were about to embark on a historic policy that would lead to regular random drug testing, Ken Caminiti dropped a bombshell: He had used steroids in 1996, the year he won the National League’s Most Valuable Player award playing third base for the San Diego Padres.

Furthermore, he posited that upward of 50 percent of players in MLB at the time were using some sort of performance-enhancing drugs. Pitcher Curt Schilling later supported that number.

That means Clemens won seven Cy Young Awards pitching against players such as Bonds, who won a record seven MVPs. Furthermore, both All-Stars hit and pitched against other players suspected of doing the same thing.

No scientific survey was ever conducted, but what became obvious was that no one covering the game or working inside the game knew exactly who was “juicing.” The field was essentially balanced.

There were obvious candidates. McGwire told Tom Verducci of Sports Illustrated in 1998 — the year of the great home-run race between McGwire and Sammy Sosa — that his forearms were 17 inches in circumference.

“I sat there thinking, “this guy’s forearms are thicker than my neck,”’ Verducci wrote.

It was the same with Bonds, whose upper body bulked up like a cartoon character, The Incredible Hulk.

Make no mistake, both players did an incredible amount of work in the weight room before and after games. Bonds said at the time he regularly bench-pressed 500 pounds. The hypothesis was the drugs they were using, plus human growth hormone, were giving them the capacity to do that work, plus recover on a much quicker basis.

Those drugs were on a federally restricted list and illegal to use, but before 2003 there was no drug policy in MLB to stop anyone from using them. It should be noted that despite several U.S. Department of Justice investigations into the sale and use of drugs in the sport, not one player was ever charged with using them.

In 2010, McGwire publicly apologized for using performance enhancing drugs, saying, “It’s something I’m certainly not proud of.”

Bonds and Clemens were charged with perjury regarding their alleged drug use. The charges stemmed from Clemens’ appearance before the U.S. Congress and Bonds’ grand jury testimony regarding the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative (BALCO) federal investigation. Juries ultimately cleared both. Bonds also beat an obstruction of justice charge stemming from his case in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Neither — unlike Manny Ramirez, Rafael Palmeiro, Dee Gordon and most recently Robinson Cano — ever failed a drug test.

Bonds, who no longer presses weights, has slimmed down and remains in terrific shape from his penchant of riding a speed bike about 50 miles per day on the roads of Marin County north of San Francisco. McGwire, the bench coach for the Padres, no longer looks like Paul Bunyan.

But many other players who didn’t appear to have ballooned in size appeared in MLB’s 2007 Mitchell Report, failed drug tests or admitted to using.

Former Dodgers pitcher Eric Gagne is Exhibit A. The right-hander was a mid-velocity starter with an 11-14 record and a 4.61 ERA until then Dodgers manager Jim Tracy made him a closer in 2002. Miraculously, his fastball jumped to 98 miles per hour, and he saved 152 games the next three seasons, including a record 84 in a row.

After his career ended at age 32 in 2008, Gagne talked about the secret behind his metamorphosis, though he hardly bulked up or looked like a caricature of himself. Gagne addressed the issue on a panel in March at the annual SABR Analytics Convention in Phoenix.

“Well, I knew it wasn’t right, and we have to live with the consequences,” he said. “I did what I did because I wanted to do it, and it’s very important that everyone be responsible for their own actions. I’ve made a lot of mistakes in my life and that was one of them.”

The ultimate moment of the steroid era came on April 16, 2004, at AT&T Park. Gagne faced Bonds — a pitcher who ultimately admitted to using PEDs against a hitter everyone suspected of using them.

Bonds told Gagne to throw his best fastballs to him in that circumstance and “let’s see what happens.” The moment was captured — the video played at AT&T — as Gagne appeared for the Bonds number retirement ceremony.

Bonds won the confrontation, hitting a long foul ball into McCovey Cove beyond the right-field wall, and eventually a two-run homer into the center-field bleachers.

Gagne described what happened:

“We were in Japan on an All-Star tour [in 2002] and Barry always complained about [nobody giving him pitches to hit.] I said, ‘You know what, if I get a three-run lead one time, I’ll face you, I promise.

“[Two years later], we’re up by three. I have a guy on first base and he’s on deck. I looked at him and he looked at me, he looked at the score. To me, I was at the top of my game. That was the best I ever pitched. And I think he was the best to ever walk the face of the earth. This is the pinnacle of my career, pretty much.

“So I’m going to throw as hard as I can. And I did that. The first pitch was a strike. The second pitch was a strike. After 0-2, I went up and in because he had one hole, and that was inside. He had that big, metal thing on his elbow, so I really had to go in hard. I think it was 1-2, and I’m like, ‘I got him.’ I threw that curveball back-door, and it was really good, but it was off a little bit. I wish I would have gotten that call.

“I came back in and it was the perfect pitch. He turned on it like it was nothing … it was 101 mph. He [pulled] it [foul] into McCovey Cove. There was no way you could keep that fair, but he almost did. I think he missed by five or six feet. I’m like, ‘All right, that’s pretty impressive.’ I [still] thought I got him. He hit a bomb, but way off. I got him, away. I go to 2-2 and I’m going down and away, perfect. I threw as hard as I could, and it came back a little bit over the middle. He almost hit my head off. It went out to center field, in San Francisco, [where] it’s cold. The ball doesn’t go anywhere. It just took off and it probably went out in one second. It was unbelievable.”

Bonds was baseball royalty

Bonds is the son of Bobby Bonds, the five-tool star player for the Giants who previously wore No. 25. Mays, who wore the long-retired No. 24, became Barry’s godfather when as a 5-year-old the youngster roamed the field and clubhouse at windy, old Candlestick Park and was taken under Mays’ wing.

“I used to hang out at Willie’s locker, climb over the top of it,” Bonds recently said in an interview. “We’d grab the bubble gum out of the baseball card packets at the time. I was always at the ballpark with my dad and Willie, every chance I could go.”

Bonds wore No. 24 with the Pittsburgh Pirates, not because of Mays, but because July 24 is his birthday, what he calls his lucky number.

During the Giants’ ceremony this past August, as former players, a manager and the club’s president extolled Barry’s virtues, Mays beckoned for the microphone. He wasn’t on the docket to speak, but as Duane Kuiper, a long-time Giants announcer, former player and a master of ceremonies, said:

“When Willie wants to speak, he speaks.”

Mays shunned the microphone as it was taken to his seat.

“First of all,” he said. “Where’s the podium at?”

Mays was led to the podium and there he made his case.

“There’s no doubt that this guy deserves the honor of being in the Hall of Fame,” Mays told a sellout crowd of 41,206. “When you get to the Hall of Fame, the honor is so big it makes you wonder, ‘How did I get here?’ I want him to have that feeling.

“So, on behalf of all the people in San Francisco and throughout the country, vote this guy in.”

Peter Magowan, the former Giants managing partner, wholeheartedly agrees. He’s 76 now and still a Giants investor.

Magowan was the driving force behind signing Bonds away from the Pirates as a free agent in 1993 and had more internal battles with the cantankerous Bonds than anybody. The signing was the lynchpin to rebuilding a franchise, which was ticketed for a move to St. Petersburg, Fla., before Magowan’s group stepped in and kept it in San Francisco.

“I think he should be in the Hall of Fame,” said Magowan while in the Giants’ dugout on Aug. 11. “He’s the best player I ever saw play baseball except for Mays. Many, many great ballplayers who played against him say he’s the best of his generation. And that’s without question.”

Bonds, with the 762 homers and 514 stolen bases, is the only 700/500 player in baseball history.

Who isn’t in?

As of 2018, absent from the Hall are the all-time hits leader, the all-time home run leader, the pitcher with the second-most wins of his generation, the only man to hit more than 60 homers in three different seasons and a member of the 500-homer, 3,000-hit club.

Pete Rose, with 4,256 hits, is banned for betting on baseball. Palmeiro, with 569 homers and 3,020 hits, failed a drug test in 2005 and never returned after his suspension. He was on the BBWAA ballot for four years before being dropped for not retaining the requisite 5 percent.

Sammy Sosa, the guy with three 60-homer seasons, is barely hanging in, last year gaining 7.8 percent. Like Bonds and Clemens, he has four more years remaining on the writers’ ballot.

In 2015, Commissioner Rob Manfred denied reinstatement for Rose from his lifetime suspension from Major League Baseball for betting on the game as manager of the Cincinnati Reds. In his well-reasoned legal brief, Manfred, a labor lawyer, proffered the suspension was independent from Rose’s Hall eligibility.

“In fact in my view,” wrote Manfred, “the considerations that should drive a decision on whether an individual should be allowed to work in baseball is not the same as those that should drive a decision on Hall of Fame eligibility. … Thus any debate over Mr. Rose’s eligibility for the Hall of Fame is one that must take place in a different forum.”

There has been no debate since. The Hall of Fame’s stance is Rose is not eligible because he remains suspended from Major League Baseball.

As far as the debate about players cast under the shadow of the performance enhancing drugs era are concerned, in 2014, the Hall’s board of directors voted to cut the period of eligibility for players on the BBWAA ballot from 15 years to 10, thus diminishing the opportunity for any candidate to be elected by one-third.

Last fall prior to the vote for the Class of 2018, the Hall distributed a letter via email from Hall of Fame second baseman and Hall board of directors member Joe Morgan to all eligible BBWAA voters.

His message couldn’t have been more succinct.

“We hope the day never comes when steroid users are voted into the Hall of Fame. They cheated. Steroid users don’t belong in here,” Morgan wrote.

One writer publicly stated he would no longer vote in the wake of the Morgan letter. There’s no way to gauge whether the 422 ballots cast were directly affected by Morgan’s opinion.

This we do know: Bonds and Clemens are tracking higher. Clemens went from 54.1 percent in 2017 to 57.3 in 2018. Bonds increased from 53.8 to 56.4. In 2014, both started in the mid-30s.

Even more significantly, Mays has now made a very strong public statement about his godson’s Hall qualifications that directly counters Morgan’s general opinion.

As a Hall of Fame voter since 1992, here’s the real question: Decades from now, when we are all gone, and kids are going to Cooperstown, do we really want them to wonder why a generation of the game’s greatest players was not included?

Paraphrasing Mays, let’s vote them in.

Barry M. Bloom has been a baseball writer since 1976, and a National Baseball Hall of Fame voter since 1992. His sometimes award-winning national reports and columns appeared on MLB.com for the past 16 years, until recently. He’s now a contributing columnist for Forbes.com.

Related Articles

Epstein: Testing positive for PEDs not a career-ender for minor-league baseball players

Has WADA helped or hurt the anti-doping movement?

From MLB to youth sports, baseball sees increased arm injuries in pitchers