America's pastime helped interned Japanese-Americans pass the time

Major League Baseball likes to recognize and celebrate its accomplishments. In the case of Jackie Robinson and integration, the professional sport was well ahead of the curve on civil rights.

The self-proclaimed “national pastime” also has been referred to as a mirror on American society and a vehicle of cultural assimilation for waves of immigrant classes.

But Major League Baseball, like the rest of the country, is also marred by a legacy of exclusion and racism regarding not only African Americans but also Asian and Latin Americans.

An International Pastime

Baseball has been popular in Japan almost as long as it has been the national game in the United States. The game was introduced to Japan in the 1870s by an American school teacher named Horace Wilson, who was teaching English to Japanese children at Kaisei Gakko School, which is now the site of Tokyo University.

Before the end of the 19th century, baseball had become Japan’s most popular sport. Many Japanese immigrants to the United States brought their affinity for the game with them.

The Excelsiors ballclub, formed in Hawaii in 1899, was the first American team comprised of Japanese immigrants. The Fuji club of San Francisco was the first team of first-generation (Issei) Japanese immigrants formed on the mainland in 1903, the same year as Major League Baseball conducted its first World Series.

At the same time, anti-Japanese movements were on the rise in cities such as San Francisco. The Asiatic Exclusion League, an organization that aimed to prevent immigration of people from Asia, was formed in 1905.

Like African-Americans, who were systematically segregated from the game for no other reason than their race, Japanese players formed their own professional leagues. In the decades to follow, segregated Japanese teams and leagues continued to thrive and prosper in California and the Pacific Northwest.

The 1920s and 1930s are considered the “Golden Era” of Nisei (second generation) Baseball, when leagues thrived in Japanese-American communities along the Pacific Coast and Western mainland.

[masterslider id="4"]

During this period, Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans struggled to be fully accepted into American society. In 1922, the Supreme Court declared Asian immigrants ineligible to become naturalized U.S. citizens on the basis of race. In 1924, the Immigration Act (also known as the Quota Act) was signed into law, effectively ending Japanese immigration into the United States.

Baseball continued to play a significant role in developing the cultural identities of Japanese-American communities, but the bombing of the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941 and the entry of the U.S. into World War II rocked the foundations of Japanese-American life.

In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, initiating the mass removal and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese and others into 10 detention camps across the country.

Zenimura “The Dean of the Diamond”

Five Japanese internment camps were located in Arizona during World War II. The Gila River War Relocation Center, located in Pinal County approximately 30 miles southeast of Phoenix, comprised two camps named Canal and Butte. The Poston War Relocation Center near Yuma, in what is now La Paz County, contained three camps.

The population at Gila River was 13,246 at the beginning of 1943. Poston was the largest of the 10 camps in the country containing 17,107 evacuees. The two camps immediately became the third and fourth largest cities in Arizona at the time.

For Japanese-Americans already familiar with the game, baseball played an important part in lending a sense of normalcy to a traumatic situation. It served as a means of passing the long hours each day.

“It was demeaning and humiliating to be incarcerated in your own country. Without baseball, camp life would have been miserable,” George “Hats” Omachi said in a 1998 interview. Omachi was a lifelong baseball man and a second-generation Japanese-American who played in the Japanese American league in Fresno, Calif., after World War II. He later worked as a major league scout.

All five camps in Arizona had baseball teams that played against each other in the intercamp league competition. That allowed the prisoners to leave the camps for games from 1943-1945.

The intercamp leagues were the brainchild of Kenichi Zenimura, perhaps the most significant figure in Japanese-American baseball history.

An accomplished player, manager and promoter, Zenimura was a veteran of the Japanese American baseball leagues in California and an organizer of international touring teams and tournaments from the mid-1920s to the late 1930s. Zenimura assisted in arranging tours of Negro League All-Star teams in Japan and barnstorming tours of major-leaguers including Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in California.

Zenimura and his family were detained first at the Fresno, Calif., fairgrounds and later in Gila River, Ariz. In both locations, Zenimura led the construction of baseball fields and surrounding ballparks, organizing a 32-team league of intercamp competition that allowed uniformed players to travel from state-to-state at time when Japanese American citizens were not allowed to do the same.

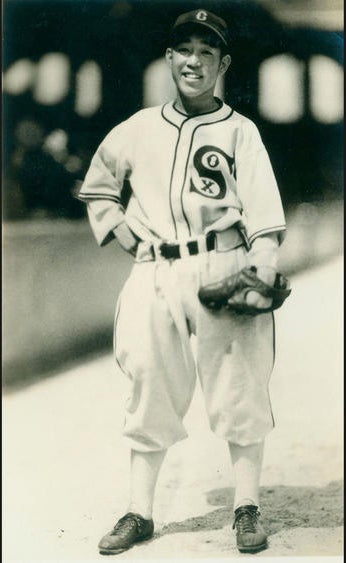

Kawano’s career in baseball began in 1933 when he stowed away on a ship carrying the Chicago Cubs to Catalina Island, off the California coast. The Cubs were on their way to spring training. Kawano was immediately put to work shining the team’s shoes. In years to follow, Kawano was hired as the White Sox spring training bat boy in Pasadena, Calif. He was believed to be the first Japanese bat boy in the major leagues.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Kawano’s family was sent to the Poston War Relocation Center on the Colorado River Indian Reservation near Yuma in hot and dusty southwestern Arizona.

While interned, Kawano wrote a letter to Chicago White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes, who had befriended him during his spring training stint as bat boy.

With Dykes’ intervention, Kawano was released from the internment camp and traveled to Chicago. He was hired by the Cubs as a clubhouse assistant in 1943 and 1944 before enlisting in the U.S. military where he served as an intelligence officer working as a translator in the Philippines and New Guinea.

Kawano returned to the Cubs after the war as clubhouse assistant until being appointed clubhouse manager in 1953.

Kawano spent more than six decades working for the Cubs. He was inducted into Arizona’s Cactus League Hall of Fame shortly before his death in 2018.

At the time of his internment, Zenimura was already considered the “Dean of the Diamond,” a nickname he was tagged with in Japanese American baseball circles. A 5-foot, 105–pound catcher, Zenimura was born in Hiroshima, Japan, and was 8 years old when his family emigrated from Japan to Hawaii. It was in Hawaii that he was introduced to baseball, immediately developing his lifelong passion for the game.

In his seminal work, “Kenichi Zenimura: Japanese American Baseball Pioneer,” author Bill Staples Jr. described Zenimura’s situation upon arriving at the Gila River relocation center:

“Zenimura was not a happy man when he first stepped foot in Gila. ‘Kenichi was so frustrated that he did nothing for two weeks, didn’t even open his suitcase,’ ” said his wife, Kiyoko. “After all his friends were sent to the Arkansas camp, and here we were in Arizona. …”

“In November 1942, Zeni’s perspective on the situation took a turn for the positive. Where others at Gila River only saw barbed wire and miles of desert, Zeni began to see potential. He ‘envisioned a baseball stadium, complete with bleachers, dugouts and an outfield wall’ ‘Finally he started to walk through the desert and sagebrush, looking out over the horizon,’ Kiyoko said.’”

Extreme desert heat and intense sunlight made for nearly impossible conditions for creating a grassy green baseball field. Utilizing innovative instincts, Zenimura’s Field of Dreams began to take form; a ballpark that served not only players and the creation of leagues but as a gathering place for the displaced members of the community who would pay to watch the games.

Tapping into a water line outside the Block 28 barracks, he channeled its flow 300 feet outside of the barbed-wire fence to water the Bermuda grass seed that became the outfield. An irrigation ditch was carved from this main line to water castor bean shrubs that grew 8 feet tall and became the outfield fence.

The ballpark would not have been complete without grandstand seating and covered dugouts.

In Staples book, he wrote: “Zenimura announced that he and other builders of the block 28 baseball field needed the help of Butte residents in collecting scrap lumber to build bleachers. He asked residents to stack scrap lumber by their block manager’s office where he would picked it up later. The bleachers were the key in turning Zenimura’s field into a stadium, with numbered seats and higher prices charged for those close to the action.

Actor Pat Morita (of “The Karate Kid” and “Happy Days” fame) also was interned at Gila River and recalled when Zenimura built his field.

“I remember this little old man out there every day watering the infield,” Morita said in 1998. “One of the great sounds of joy for me was the sound of baseball.”

Staples wrote: “The first game played on “Zenimura Field” was a preseason scrimmage on Feb. 23, 1943 between Guadalupe Club and Zenimura’s own Block 28 team, two of the seven teams that comprised the Canal Athletic Society (CAS) League. Official league play began with a doubleheader between the same two clubs on March 6 and was covered by the camp’s Gila News Courier newspaper: “That Zenimura ball diamond certainly is some humdinger. Makes us remember the good ole days back home. ”

In one of the most significant meetings with an outside team, the 1945 Butte Eagles high-school all-star team -- with two of Zenimura’s sons -- defeated the Tucson High School Badgers 11-10 in a 10-inning exhibition game. Tucson High was one of the top teams in the state, having won 12 state titles at that point.

Film and Studies

Kerry Yo Nakagawa is the founder of the Nisei Baseball Research project, a non-profit 501(c)3 organization designed to preserve the history of Japanese American Baseball, and producer of the 2007 film American Pastime, a docudrama based on Kenichi Zenimura and his family’s experience at the Gila River internment camp and the creation of his baseball field and league.

He is also the author of “Through a Diamond, 100 Years of Japanese American Baseball” and “A History of Japanese American Baseball in California” and curator of the touring “Diamonds in the Rough: Japanese-Americans in Baseball” exhibition, which was displayed at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown and the Arizona State Capital. Nakagawa also has developed an educational curriculum of the same name.

“For Japanese-Americans interned during World War II, playing, watching and supporting baseball inside of America’s concentration camps brought a sense of normalcy to very ‘abnormal’ lives and created a social and positive atmosphere,” Nakagawa said. “Japanese-Americans kept the national pastime alive, even behind barbed wire. In their world, life brought a desert and … they built “Diamonds in the Rough.”

Charlie Vascellaro is a frequent presenter and speaker on the academic baseball conference circuit. Author of a biography of Hall of Fame slugger Hank Aaron, Vascellaro’s baseball and travel writing has also appeared in the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Baltimore Sun, Arizona Republic. Vascellaro has written on social and cultural issues pertaining to baseball for the MLB.com, ESPN W, La Vida Baseball, Spitball magazine and the Smithsonian Institute’s Museum of the Native American magazine.