Black athletes face bias when seeking medical care

The new mother lay in the hospital, recovering from an emergency C-section the previous day. She started to feel short of breath and immediately knew the cause.

Serena Williams, professional tennis player, had a history of blood clots and at that moment, she immediately assumed she was having another pulmonary embolism because she was off her medication, due to the recent surgery.

In between gasps, Williams told her nurse that she needed a CT scan with contrast and IV heparin (a blood thinner) immediately. The nurse assumed that her medication was making her confused, but Williams insisted. A doctor performed an ultrasound on her legs that revealed nothing. They sent her for the CT and sure enough, it showed several small blood clots that had settled in her lungs.

Minutes later, she was put on an IV. “I was like, listen to Dr. Williams!” Serena told Vogue.

African-Americans are routinely undertreated for their pain compared to white patients. A study in 2016 shed alarming light on why this might be the case.

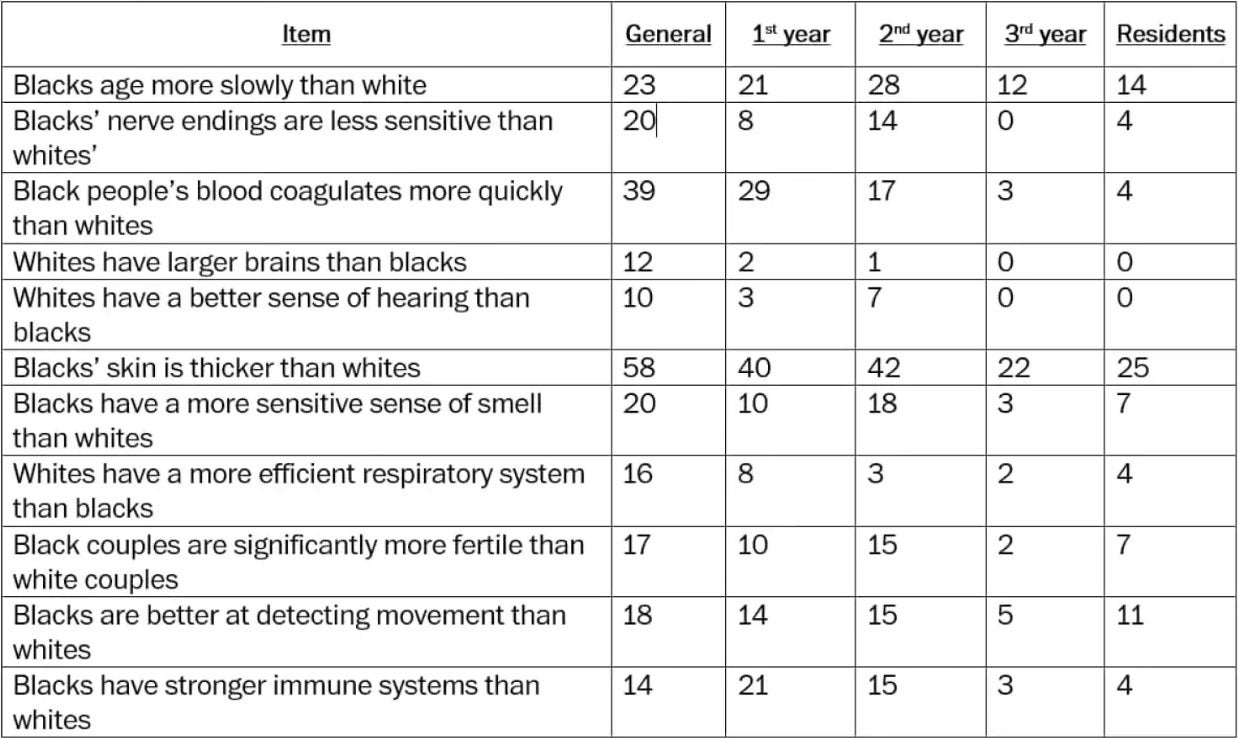

Researchers at the University of Virginia tested 222 white medical students and residents to see how many of them perceived inaccurate and, at times, fantastical differences between the two races — for example, that black people age slower than whites, that their nerve endings are less sensitive to whites or that their skin is thicker than whites.

The researchers found that half of the sample advocated at least one of the false beliefs and those who advocated these beliefs were more likely to record lower pain ratings for black patients as opposed to white patients, and were less accurate in their treatment recommendations.

Comparably, a 2017 study looked at race and sports, specifically racial bias in the sports medicine field. Researchers studied the intersection of racial bias in pain-related perceptions among NCAA Division I sports medical staff. The study showed medical staff perceived black athletes as feeling less pain than white athletes did; furthermore, they perceive basketball players as feeling less pain than soccer players.

“If you’re really dedicated to science, that makes no sense,” Dr. David Satin, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota Medical School, said. “Even if race is biological, that makes no sense. I am disturbed by the fact that so many people endorse that.”

Satin is a professor who teaches courses on topics of race, and he said this study underscores the importance of properly teaching medical students to think critically about race and to understand how implicit bias impacts medical care.

“It is not uncommon at the beginning of the course to have a block of students that are resistant to the idea that unconscious bias really exists,” said Swapna Reddy, a Clinical Assistant Professor at Arizona State University’s School for Science of Health Care Delivery, College of Health Solutions. “You really see a transformation and shift in the students. I always say they’re allowed to think any way they want but they need to be aware of what evidence says.”

Reddy has done years of research in this topic and said the first, and most important, step is awareness of the issue. Although the majority of people will never admit to being racist or bias, an overwhelming amount of clear evidence shows how unconscious and implicit bias can alter the thought process.

The UVA study could help illuminate the problems in pain treatment today: White people are more likely than black people to be prescribed stronger medications for the same medical problem.

“Many previous studies have shown that black Americans are undertreated for pain compared to white Americans,” Kelly Hoffman, a UVA psychology Ph.D candidate who led the study, told UVA Today. “Because physicians might assume black patients might abuse the medications or because they might not recognize the pain of their black patients in the first place. Our findings show beliefs about black-white differences in biology may contribute to this disparity.”

In the experiment, the researchers asked white medical students and residents to rate on a scale of 10, the pain level they would associate with two mock medical cases: a kidney stone and a leg fracture. The participants had to rate the two cases for a black and white patient’s pain level and recommend pain treatments based on the level of pain they thought the patient was enduring. The results shed light on an unexplored area of racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations within a relevant population.

“We’ve known for a long time that there are huge disparities in how blacks and whites are assessed and treated by the medical community,” Hoffman said. “Our study provides some insight to what might contribute to this — false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. These beliefs have been around for a long time in our history. They were once used to justify slavery and the inhumane treatment of black people in medicine.”

Hoffman said that, to her knowledge, this is the first study that connects racial bias about biology, racial perception of pain and the accuracy of medical advice.

The University of Virginia study supports arguments that physician bias is a factor. The study had two parts: one looked at a random sample of 92 white people from across the country. The second looked at 222 medical students and residents at the university. In both parts, participants were given statements that had accurate or inaccurate information about the biological differences between white and black people.

“We were expecting some endorsement” of the false beliefs, Hoffman said. But she said the researchers were surprised so many in the group with medical training endorsed the false beliefs, some of which she called more outlandish.

In the study, 58 percent of the study’s general group said the statement: “blacks’ skin is thicker than whites” is true. Around 40 percent of first- and second-year medical students also thought that was a true statement, as did 25 percent of residents.

According to Keith Wailoo, author and professor at Princeton University, the study highlights how mistaken attitudes — about race, pain and biology — can flourish in one of the worst possible places: medical schools where the future gatekeepers of relief are being trained. Wailoo defines it as the divided state of analgesia in America, which is the overtreatment of millions of people that feeds painkiller abuse while, with far less public attention, millions of others are systematically undertreated.

“The relief of pain is obviously one of the main functions of physicians,” Frank Ervin, a Boston psychiatrist, said in 1959. “Ironically, it's one of the things we do least well — partly because we don't understand it."

In another case, a study published in 2015 by the JAMA Pediatrics Network led by Monika K. Goyal found black children with appendicitis were less likely to receive pain medication than white counterparts. And in 2007, researchers found physicians were more likely to underestimate the pain of black patients compared with other patients.

Another study released by the Group Processes & Intergroup Relations analyzed findings to detect whether people assume that those who have faced hardship feel less pain than those who have not and whether this belief contributes to the perception that black people feel less pain than white people. The researchers, Kelly Hoffman and Sophie Trawalter, found racial bias emerged but only when the hardship information was consistent with expectations about race and life hardship. The experiments suggest that perceptions of hardship shape perceptions of pain and contribute to racial bias in pain perception.

Satin said he was disturbed to find how many medical students and residents agreed with some of the false beliefs about black people’s biology, such as the belief that black people age more slowly than white people, with which 28 percent of surveyed second-year medical students agreed.

Researchers suggest perceptions of socioeconomic status can explain these biases in perceptions of pain in the population because people assume black people have less pain but only if and when they assume black people have lower socioeconomic status.

Researchers who study health disparities have said unconscious stereotypes about African-Americans contribute to the problem, as well as physicians’ difficulty empathizing with patients whose experiences differ from theirs.

In 2011, a National Academy of Medicine report on pain concluded that in medical education, pain generally has received little attention which ultimately contributes to the problem of undertreatment. The report on unrelieved pain called for “a cultural transformation in the way pain is viewed and treated.”

According to a post on Statnews.com, collaborations are underway, by researchers and medical schools, to look at whether educating students differently can reduce racial bias in treatment accuracy and pain perception.

Logan Huff is a senior journalism major at Arizona State University.

Related Articles:

Serena Williams on Motherhood, Marriage, and Making Her Comeback