Study shows student-athletes hesitant to report PED abuse

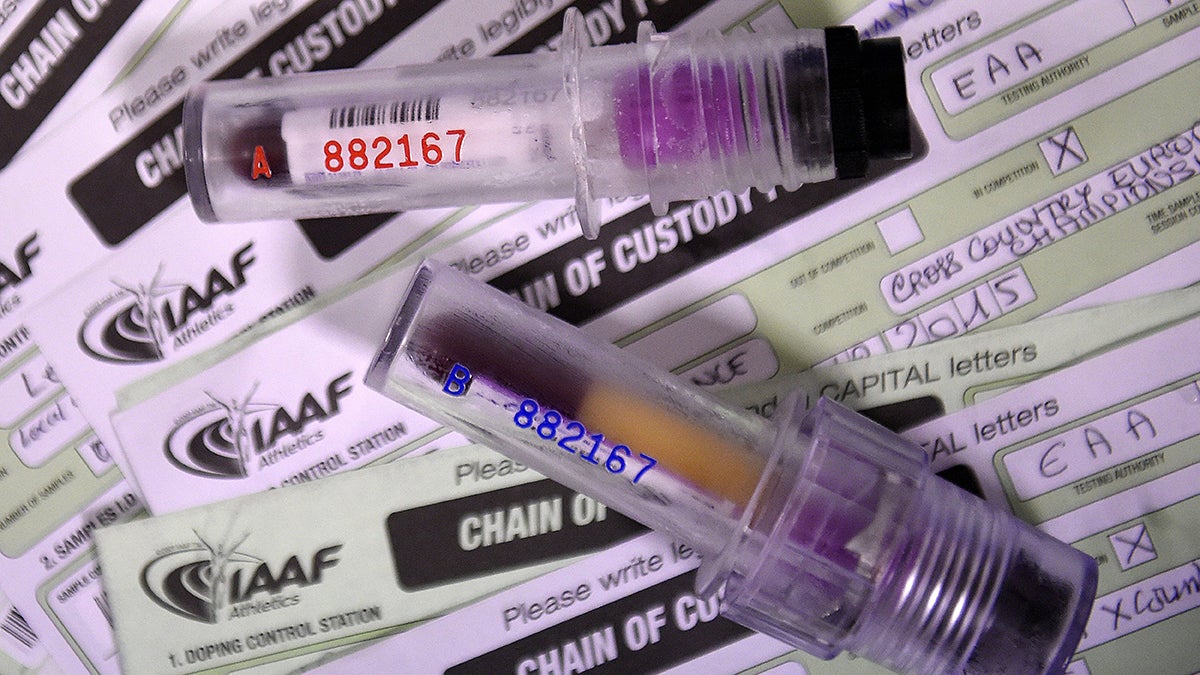

In 2015, the former head of Russia’s anti-doping laboratory, Grigory Rodchenkov, exposed Russia’s tampering of blood and urine samples to cover up their use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs).

Rodchenkov, who resigned from his position after the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) accused him of tampering with more than 1,400 samples before the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, fled Russia with his family out of fear for their safety.

This is an extreme example of why people may refrain from whistleblowing, but it is not the only reason.

Since 2016, track and field athletes have received the most doping sanctions worldwide. Researcher Kelsey Erickson conducted a study of 28 collegiate level track and field athletes from the United States and the United Kingdom. Fourteen athletes from each country were asked four questions about their views on PED usage and how they would react to knowing a teammate or competitor was using illegal substances.

The study participants knew that doing PEDs was wrong and stated they would not use them. However, whether or not they would report another athlete varied depending on the situation.

“It seems choices regarding blowing the whistle on doping are not dependant on titles but, rather, relational factors,” Erickson said.

The athletes were more inclined to keep the secret of a close teammate than of someone they did not have a friendly and close relationship with. Coinciding with these results, athletes said they were more likely to address the person who was abusing the substance or report the PED abuse to a superior who was not affiliated with the anti-doping efforts than to WADA.

In recent years, WADA has attempted to focus on doping prevention through an intelligence-driven approach.

“Doping prevention requires a multifaceted approach that involves testing, education, ongoing conversation and intelligence-led investigations,” Erickson said. “The anti-doping landscape is constantly moving, and it is a complex issue, so the approach to deterrence cannot be stagnant – it has to constantly evolve and grow.”

Despite millions of dollars devoted to PED prevention and deterrence, PEDs remain pervasive in the sports world. The study indicates student-athletes find a community-based, personally-addressing-the-user approach more appealing than whistleblowing or reporting the athlete. This raises the question moving forward whether efforts should be focused on encouraging confrontation to stop PED use rather than the original methods.

Lauren Chiangpradit is a junior sports journalism major at Arizona State University

Editor’s note: For the coming 2019-2020 academic year, the Global Sport Institute’s research theme will be “Sport and the body.” The Institute will conduct and fund research and host events that will explore a myriad of topics related to the body, including the use of performance enhancement techniques.

Related Articles

Has WADA helped or hurt the anti-doping movement?

Aussie anti-doping agency can now hack athletes’ phones

Push to allow professional athletes took hold in 1968 Olympic Games

IOC’s policy on athlete medical marijuana use looser than U.S. sports leagues

Mexico City Games became launch pad for athlete doping tests