Baseball, Basketball, and Beyond: How ASU Research on Action-Specific Perception Can Help Resolve Real-World Disputes

Why this matters

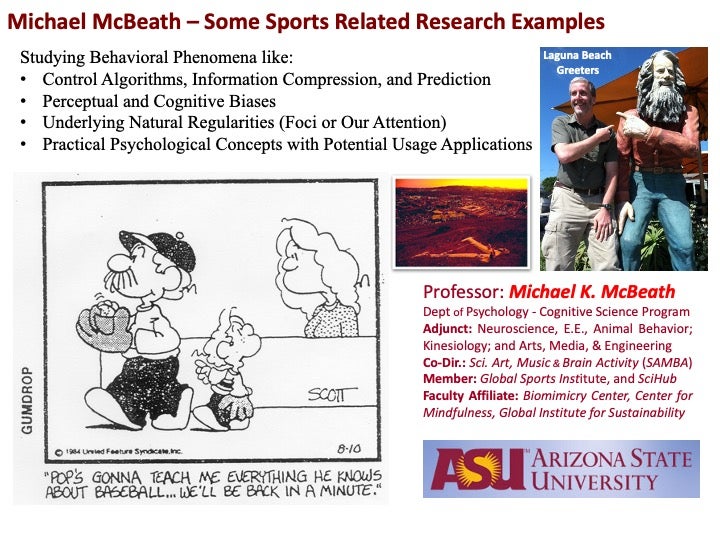

Sports can provide a useful conceptual framework for analyzing larger issues of human behavior and psychology. Focusing on the role that vantage points play in our perceptions in relation to popular American sports, the work of Dr. Michael McBeath, a Global Sport Institute Scholar, shines light on multiple paths forward for dispute resolution.

In an era where terms like “partisan,” “polarized,” and “baseless” are nearly as ubiquitous as air and water, revisiting a controversy from Game Six of the 1985 World Series to illustrate how vantage points influence our perceptions seems almost quaint. And yet, it is instructive – in the context of both sports and the wider world.

To recap, the host Kansas City Royals, facing the St. Louis Cardinals, were en route to becoming just the fifth baseball club in history to rally from a 3-1 World Series deficit and win it all. With St. Louis leading 1-0 in the ninth inning, Kansas City’s Jorge Orta hit a grounder into the right infield, where St. Louis’s Jack Clark scooped up the ball and threw it to Todd Worrell at first base. Umpire Don Denkinger called Orta safe. The Cardinals argued but the controversial call stood – even though instant replay, which Denkinger could not access, clearly revealed that Orta was out.

This is where Dr. Michael McBeath’s work comes in. To quote the official biography of this veteran Arizona State University professor and Senior Global Sport Institute (GSI) Scholar, he “does research in the emerging area combining psychology, engineering, and perception-action,” specifically focusing on “computational modeling of perception-action in dynamic, natural environments, with specialties that span sports, robotics, music, navigation, animal behavior, and multi-sensory object perception.”

In 2017-18, McBeath, whose extensive academic credentials include a PhD from Stanford in psychology with a minor in electrical engineering, received a GSI seed grant providing $18,000 in funding to continue applying his work on action-specific perception to sports phenomena.

He served as an advisor on a 2018 master’s thesis by ASU graduate teaching assistant R. Chandler Krynen, entitled “Baseball’s Sight-Audition Farness Effect (SAFE) When Umpiring Baserunners: Judging Precedence of Competing Visual Versus Auditory Events.” It helps us understand what might have been going through the mind of a Royals fan seated far from the field in the Kansas City crowd of 41,628 on October 26, 1985.

The abstract of the paper, which appeared in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, notes: “Baseball umpires judge force-outs at first-base by comparing the sound of ball-mitt contact to the sight of foot-base contact ... distant fans will tend to have more of a bias to experience baserunners as safe, compared with nearby umpires.”

In the 1985 case, Denkinger gave a straightforward explanation for his error to Sports Illustrated: “I was in good position, but Worrell is tall, the throw was high, and I couldn’t watch his glove and his feet at the same time. It was a soft toss, and there was so much crowd noise, I couldn’t hear the ball hit the glove.”

Now, consider our hypothetical Kansas City fan. Let’s assume it’s a man who is deeply invested in the Royals success – a native of Kansas City who played Little League, an MLB season ticket-holder, full of civic pride, dreaming of seeing his team win its first World Series both for historical glory and for spin-off economic benefits. Since it might appear from this fan’s distant vantage point that Orta’s foot touched the base first, and since the sound of the ball hitting Worrell’s mitt would have reached his ears later even if it was not drowned out by the crowd, he would have every reason and incentive to support the umpire’s wrong call vociferously. This being 1985, he would also have no smartphone on which to immediately check out the replay.

And yet, the research McBeath oversaw – which included testing the responses of 70 ASU undergraduate students to audio and visual stimuli – would provide a solid, empirical basis for disabusing our Royals fan of his erroneous assessment. At the same time, it would provide an understanding of and validation for why that fan perceived what he perceived.

In a related vein, McBeath’s 2019 collaboration with ASU graduate student and Global Sport Scholar Ty Tang, “Who hit the ball out last? An egocentric temporal order bias,” makes a point that’s particularly applicable to basketball players disputing who touched the ball last before it went out of bounds: “We find a robust bias to perceive self-generated action events to occur about 50 [milliseconds] before external sensory events. We denote this bias to perceive self-actions earlier as the ‘egocentric temporal order’ bias. Thus, if two players hit a ball nearly simultaneously, then both will likely have different subjective experiences of who touched last, leading to arguments.”

An important recurring theme in McBeath’s work is the distinction and relationship between viewpoints that are egocentric (essentially, what you personally see) and allocentric (a viewpoint established on the basis of external factors).

A cheeky pun in 2018’s “The geometry of consciousness” – co-authored with Tang and the Ohio State University researcher Dennis M. Shaffer – frames that distinction in terms of two seminal historical figures: “Perhaps the most well-known contribution to the study of consciousness by Descartes is his famous quote, ‘Cogito ergo sum’ - I think therefore I am. What is not as well known is that 17 centuries earlier, the Roman Poet, Horace, lyricized, “Non sum qualis eram” - I am not what I was (Ferry, 1998). Though the earlier quote may not be as prophetic, the historical precedence makes it clear that we should not put Descartes before the Horace.”

McBeath’s findings are not only useful in terms of resolving disputes over sports minutiae or matters of purely academic interest. The Global Sport Institute’s seed grant program seeks research proposals encompassing “diverse disciplines,” including “issues, processes, or phenomena that can or will affect audiences throughout the world.”

“One of the things I really like about the way our research fits in with the Global Sport Institute is how we unequivocally show that people experience the world differently from different perspectives,” McBeath said. “This has ramifications on training and performance, but also can be seen as a metaphor regarding important social issues like racism, sexism, and so on, which are studied more by others in the Global Sport Institute.”

It is not hard to identify some analogous real-world examples. Awareness of racism in the United States, for instance, surged when TV viewers and Internet users received a new perspective via the horrifying footage of George Floyd’s death on May 25, 2020 when a Minneapolis police officer kneeled on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes.

Someone who views Hollywood through an egocentric lens might surmise that female representation on-screen has skyrocketed in recent years with hit productions such as Wonder Woman and Little Women. The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, however, offers a different, data-driven viewpoint. Findings in 2019’s “The Geena Benchmark Report: 2007-2017” noted that in the top-grossing 100 family movies during that period, male lead characters (71.3 %) significantly outnumbered female lead characters (28.8 %).

Climate change, gun control, and healthcare policy are just some of the other hot-button topics where greater consensus and smarter solutions could be achieved by “establishing systematic reasons why people’s experiences different in fundamental ways.”

McBeath’s co-authored 2004 Psychological Science paper, “How Dogs Navigate to Catch Frisbees,” is a personal favorite of his. Not only was the paper – which showed how dogs, like baseball players, employ a strategy of “maintaining the target along a linear optical trajectory” in order to complete the catch – spoofed on an episode of Saturday Night Live, but its central principle was also cited in a January 21, 2020 New York Times column by Thomas Friedman, where the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist offered his analysis of the most effective approach for Democrats seeking to impeach President Donald J. Trump for a second time.

“Going beyond sports, we can connect these concepts to more complicated things like what’s going on with our political debate,” McBeath said. “Those are somewhat harder variables to define. But, you know, these same kinds of principles apply. And so my work has been cited a lot by people as a general way of thinking that applies to higher level cognitive concepts. And I’m fine with that. It’s an example of how work in sports perception can be applied to greater abstract human behavior, and it seems perfectly appropriate to me.”

National Puzzle Day is Jan. 29, so it's time to engage your brain. We asked @ASU professor Michael McBeath why our brains love #puzzles. https://t.co/ZCnK4KI9SH pic.twitter.com/vpSrRwRkrB

— ASU News (@asunews) January 26, 2018

McBeath’s diverse research interests go beyond sports. They also include autonomous ball-catching robots, navigable endoscopic pill cameras, and wearable robot and mirror-based stroke rehabilitation.

However, even amid the murky waters of cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias that have been further muddied by the synapse-wearying onslaught of social media in the 21st-century, the ASU professor’s fresh insights on action-specific perception in baseball, basketball and other sports could ultimately constitute his most enduring legacy as humanity’s struggle to establish a set of common facts continues.