Blind broadcasters paint picture of play on the field

Enrique Oliu, Bryce Weiler and Matt Wallace have much in common. They grew up with a passion for sports, they live everyday feeling there is nothing they cannot accomplish and they parlayed that determination and love for athletics into becoming broadcasters.

The three have one other thing in common: they are blind.

Oliu and Weiler were born several weeks premature and with retinopathy of prematurity. The condition left their retinas undeveloped and with the ability to only perceive light. Wallace was born with bilateral anophthalmia, a rare condition in which optic nerves never develop, resulting in empty eye sockets. None of this prevented either of them from following their dreams in becoming the eyes of listeners.

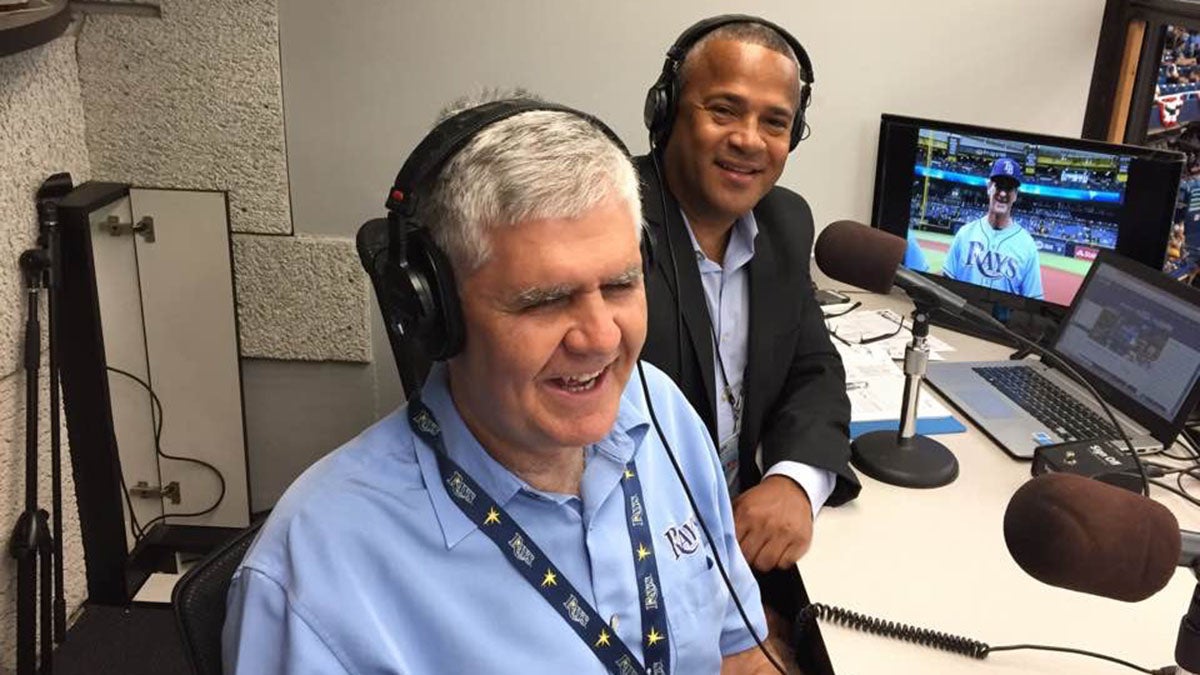

“I always wanted to do this,” said Oliu, in his 20th season of calling games for the Tampa Bay Rays’ Spanish radio network. “This was my dream. I was always interested in sports and I loved the radio.”

The radio, the method older generations used to consume and fall in love with sports, is the medium through which each of them developed their love of sports. As a youngster Weiler listened intently as Brian Barnhart called the action on the hardwood and gridiron for the University of Illinois or Don Fischer doing the same for the University of Indiana.

“Those were two commentators who brought sports to life for me by giving me a picture of the game happening on the court or on the field,” said the 27-year-old Illinois native. “It was through listening to those games that I really began to understand sports and understand how basketball players could pass the ball down the court.”

Weiler will spend a second summer in Connecticut working as a commentator for the New Britain Bees of the independent Atlantic League of Professional Baseball.

Oliu, who also works in the Hillsborough County public defender’s office in Tampa, has a sports radio resume that dates to 1989 when he was with the Jacksonville Expos minor league baseball team. He admired the work of the late sports broadcasting icons Harry Caray and Jack Buck, among others.

Oliu, who received a degree in communications from the University of South Florida, learned baseball in gym class and was a member of the wrestling team for three years at the Florida School for the Deaf and Blind. FSDB, located in St. Augustine, counts Ray Charles among its alumni.

“At (FSDB) I got to learn and play sports,” said the 56-year-old Oliu, who was born in Nicaragua, moved to Costa Rica at age 5 and then Florida when he was 10 so that he could attend FSDB. “I got a feel for sports because we were taught how to play them.”

Wallace, who in February wrapped up his first season as commentator on internet audio feeds for the University of Pennsylvania’s women’s club ice hockey team, was on the swim team at his Catholic high school outside Philadelphia.

While Oliu and Wallace may not have seen the action unfolding around them, those who are totally blind or visually impaired can still participate and thrive in athletics.

“We have the kids participate in games so they can kind of get an orientation to the field of play,” said Dr. Jeanne Prickett, who is in her sixth year as president at FSDB and has spent more than 40 years educating those with total or partial sight and hearing loss. “When it comes to baseball, they can play T-ball or play with a beeper ball. At first they can get somebody to walk the bases with them and then find out where all the positions are so that they can acquire a sense of what is going on. They can then play the game. It is not easy and it is not as seamless as when sighted folks play, but it is enjoyable and engaging.”

Though they cannot see a player driving the lane for a dunk, a center fielder racing back to the warning track to make a catch or a goalie sprawling across the crease to make a save, audio cues provide a sense of the action. These cues can be play-by-play description, microphones on or near the playing surface, crowd reaction – or as Oliu said, “the crescendo of the fans” – and a referee’s whistle and infraction call.

“I rely on any kind of verbal cues that I can and mainly my fellow play-by-play guy,” said the 27-year-old Wallace, who grew up listening to all four major Philadelphia sports teams. “I know exactly what is going on in the game based upon his description. I can then pick up on the game and analyze it. I also grew up listening to a lot of (Philadelphia Flyers) hockey on the radio and I picked up different things from those broadcasts.”

“It’s well known that people with disabilities such as hearing loss or vision loss compensate by having an increase in their other sentences,” said Dr. Anikar Chhabra, the director of sports medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix and associate professor at the Mayo College of Medicine. “The best way to describe it is that people who can’t see are able to pick up more subtle audio cues that other people aren’t as attuned to.”

“Blind people have to rely on hearing,” said Prickett, who like Oliu is bilingual and has listened many of Oliu’s broadcasts. “Some don’t do it very well and some do it really well. Enrique is an example of someone who has done it to the absolute ultimate.”

Play-by-play partner Sam Fryman and Wallace attended Temple University where they appeared together on the school’s television sports talk program, We Make the Call. Fryman, who was also in his first season of calling Penn women’s hockey games, handled the first couple of games solo. He thought it would be good to have a commentator and turned to Wallace. The pair was together again more than two years after graduating college.

“He made the (broadcasts) so much better,” said Fryman. “We are two different personalities. He more of a tell-it-like-is guy and I kind of just describe the action while passing along different points and questions to him.”

As with individuals with no disabilities, there are various levels of natural ability among the impaired.

Even if one’s level of audio acuity may not be as strong as somebody else’s, one thing they can all do well is their homework. Talking to players and coaches and perusing team and player notes are functions of the job description.

Chhabra also noted that the preparation these men do and the dedication they have to their work makes for high quality broadcasts.

“I’ve listened to some of these broadcasts and they are just as good if not better because they’re prepared. They know more about the backstories of the athletes and they’re able to fill in the gaps from what they can’t see with these stories,” he said.

“They create the story they see in their mind and it gives an unbelievably accurate portrayal. It’s a testament to their hard work and what they’re able to do.”

Adaptability devices in laptops and the like allow the visually impaired access to email, web pages to texts.

Preparation helped Weiler analyze games for multiple sports as an undergrad at Evansville University and as a graduate student at Western Illinois University. His level of diligence impressed Tom Benson, who is an assistant athletic director at Evansville and produces Purple Aces broadcasts. When he was first approached by Weiler in 2010, Benson felt he could work with the young man.

“I told him that if he was willing to work, then I am willing to work with him,” he recalled. “He is a man who has overcome the obstacles put before him in life and I owed it to him to work with him in order to help him achieve his goals. Whether he was talking to coaches or reading up on players, it was amazing to see how he worked and how hard he worked to improve himself.”

Weiler, who at the team’s urging has provided the Baltimore Orioles with suggestions to better accommodate seating for the disabled at Camden Yards and their spring training complex in Sarasota, went so far as to check audio archives for broadcasts if a visiting team’s notes were not to his liking. After all, doing his job to the fullest is the only thing he knows.

“I can work to get better stories about the lives of players and coaches both on and off the field and present them to people listening to the broadcast,” he said. “Just because someone does something differently because they cannot see or they are in a wheelchair, or whatever the case might be, does not mean that a person cannot fully do a job.”

Busting through those barriers is something Weiler, Oliu and Wallace have done and continue to do while encouraging others with disabilities to do so.

“It sounds cliché, but do what you want to do,” said Wallace. “If you are totally blind or legally blind you are going to hear ‘Wouldn’t it be easier if you were a lawyer or psychologist? Blind people can talk to other people, so why don’t you just do that?’ You will put up with stuff like that. But you want to wake up happy doing what you want to do. It doesn’t mean you will get your dream job within the career that you want, but never give up on that dream. Always pursue it.”

Oliu, nicknamed “The Volcano” because Nicaragua is known as “the land of lakes and volcanos,” often returns to FSDB to mentor students. He preaches the importance of pursuing goals and scaling hurdles that will present themselves along the way.

“Keep pushing,” he said. “Life is hard, but you can keep pushing. That goes for anybody. You never know what you can do if you don’t go after what you want. Who would have ever thought that I would have done this for 20 years?”

Tom Layberger has spent more than 25 years as a writer, editor and web producer for various outlets, including the Versus network for whom he managed NHL and college football content.

Emily Ducker contributed