Russia the focal point for anti-doping efforts after GDR demise

Why this matters

Controversy, corruption, and doping comes to the forefront of international sport after Russia potentially faces a ban from the 2020 Olympics.

From passing bottles of urine through a hole in a laboratory wall to launching cyberattacks on international sports organizations, the measures Russia reportedly has taken to cover up suspected athletic doping are as extreme and furtive as anything in a James Bond movie or John Le Carre novel.

Currently, in a rapidly developing story, the Russians are under fire — again — due to suspect internal handling of doping test results.

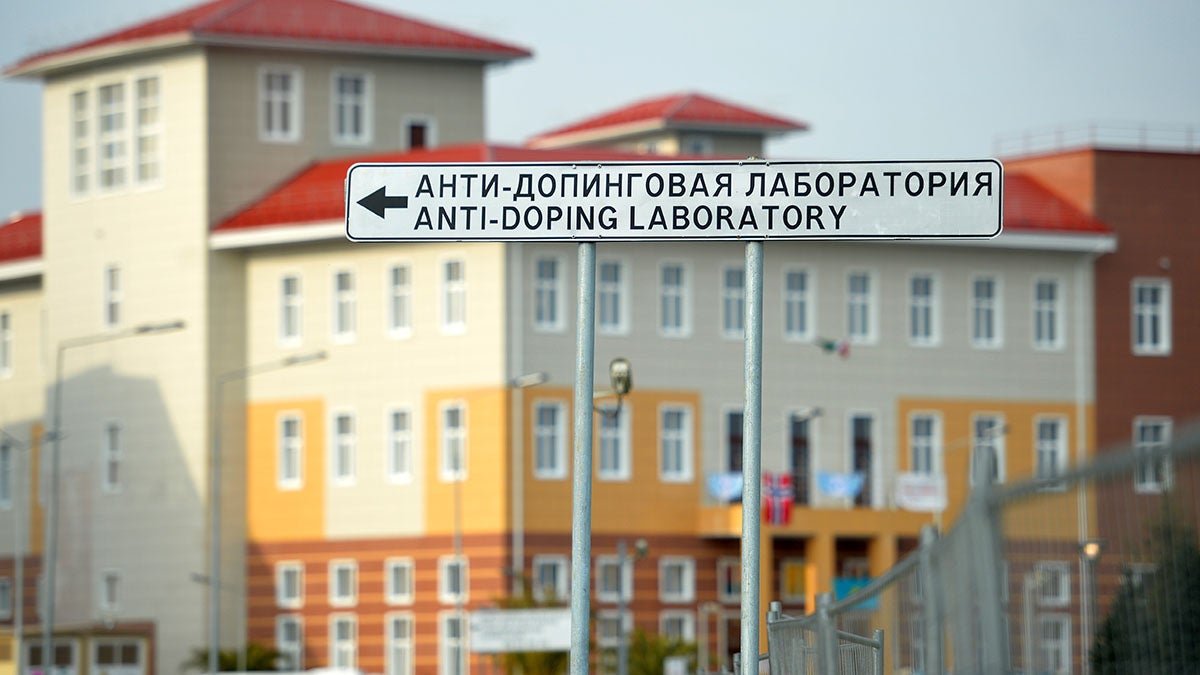

RUSADA, the Russian anti-doping agency, was suspended in 2015 and reinstated in 2018. Terms of the reinstatement included handing over data from its Moscow laboratory. However, gaps and inconsistencies, including deleted files, were detected recently.

Whether RUSADA was directly involved in manipulating that data or whether a Russian hacking group like Fancy Bear — the same group that hacked into the Democratic National Committee’s servers during the 2016 U.S. presidential election — was independently responsible, is currently being weighed by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

If WADA deems Russia non-compliant, a ban from participation in the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics could follow.

To those who recall the Cold War, this feels like a time warp. The Berlin Wall came down on Nov. 9, 1989 and East Germany ceased to exist on Oct. 3, 1990, the date of Germany’s reunification. Yet despite the end of the notorious East German athletic doping machine, Russia has revived the specter of state-sponsored doping in recent years. (Some doping administrators, like Dr. Sergei Portugalov, who got a lifetime ban from sport in 2017, were also involved back in the Soviet era.)

Controversy has particularly overshadowed Russian results at the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, the 2012 London Summer Olympics, the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics, the 2016 Rio Summer Olympics, and the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics. Overall, In the new millennium, Russian athletes have been stripped of more than 40 Olympic medals due to performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs).

Looking back, fallout from Sochi was a major catalyst. Starting in late 2014, documentaries on Germany’s ARD TV network put Russia’s successes under the microscope, uncovering an illegal morass of hormones, steroids, covered-up positive doping results, and covert payments — organized from the top down.

The Pound Report, named after a commission chaired by WADA founder Dick Pound, substantiated the scandalous findings. The independent McLaren Report, conducted by Canadian law professor Richard McLaren, offered further validation.

Bryan Fogel’s Oscar-winning 2017 documentary film “Icarus” stunned Netflix viewers with the revelations of whistleblower Dr. Grigory Rodchenkov. The former head of Russia’s anti-doping laboratory confessed on camera to spearheading systemic cheating at the 2012 and 2014 Olympics.

Methods included mixing PEDs with whiskey and vermouth as masking agents, and setting up a shadow lab in Sochi with a hole in the wall to swap out tainted urine for clean samples. Rodchenkov is now in the U.S. Witness Protection Program out of concern for his safety.

In 2016 and 2017, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) retested urine samples stored from the 2008 and 2012 Olympics. In just one example of links between the past and the present, Yuliya Zaripova, who won the 2012 Olympic women’s 3,000-meter steeplechase, was retroactively found to have used Turinabol — an anabolic steroid created in East Germany in 1961 — and disqualified.

That said, sanctions against Russian state-sponsored doping have generally been tough in theory but lenient in practice.

In 2018, the IOC suspended the Russian Olympic Committee, but Russian athletes not implicated in doping were still allowed to compete in Pyeongchang under the Olympic flag and the title of the “Olympic Athletes from Russia.” The IOC’s Oswald Commission imposed lifetime bans on more than 40 Russians who committed doping violations in Sochi, but the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), based in Lausanne, Switzerland, overturned most of those bans.

Similarly, this year the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) prohibited Russia from taking part in the World Athletics Championships for the second straight year. However, certain Russians competed in Doha, Qatar as “Authorized Neutral Athletes,” including gold medalists Anzhelika Sidorova (pole vault) and Mariya Lasitskene (high jump).

However, it’s not just Russians and former East Germans who have been implicated in large-scale doping within living memory.

Former Chinese Olympic doctor Xue Yinxian alleged that Chinese athletes were widely doped in the 1980s and 1990s. Notably, Chinese swimmers faced major PED busts in international competition in 1994 and 1998.

WADA reported that between 2004 and 2018, 138 Kenyan athletes were suspended for doping, including the likes of 2016 Olympic marathon champion Jemima Sumgong. She is now serving an eight-year ban for abusing EPO, which stimulates red blood cell production to deliver more oxygen to the muscles, and for providing false testimony.

Americans have principally fixated on high-profile cases of doping in sports like baseball (Barry Bonds) and cycling (Lance Armstrong). However, in October 2019, distance running came under scrutiny when Nike shut down its Oregon Project, an elite training group. Head coach Alberto Salazar, a former marathon champion, received a four-year U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) ban for “orchestrating and facilitating prohibited doping conduct.” (Salazar has said he will appeal to CAS.)

Even Finland — a perennial contender for the title of the world’s least corrupt nation — was shocked when six Finnish cross-country skiers, including six-time Olympic medalists Mika Myllyla and Harri Kirvesniemi, were caught blood doping at the 2001 World Championships on home snow in Lahti.

The fight against PEDs — on both the individual and state-sponsored levels — is seemingly endless. The U.S. took another step in October when the House of Representatives passed the Rodchenkov Anti-Doping Act, which, if signed into law, will criminalize doping.

Meanwhile, WADA’s decision on Russia’s doping compliance is expected in December.

Lucas Aykroyd writes for the New York Times, espnW, and the Women’s Sports Foundation. Based in Vancouver, he has covered women’s hockey at five Winter Olympics and four IIHF Women’s World Championships.

Editor’s note: For the 2019-2020 academic year, the Global Sport Institute’s research theme will be “Sport and the body.” The Institute will conduct and fund research and host events that will explore a myriad of topics related to the body.