My COVID-19 Year as a Youth Sports Parent and Why I Fear What’s Next

Why this matters

Lacking national leadership and shared safety criteria, youth sports during the pandemic have been a fragmented quagmire of some people doing their best and others ignoring common sense—leaving parents and children to fend for themselves. Will anything change moving forward?

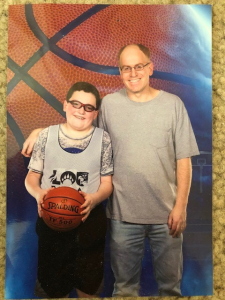

More than one year has passed since my sports-loving, 12-year-old son Josh played organized youth sports. It’s not what we want. Then again, has the coronavirus pandemic ever been about what any of us want?

The pandemic robbed Josh of his spring 2020 baseball season. As cases spiked, my wife and I didn’t feel comfortable continuing with his fall recreational soccer and baseball teams, and indoor basketball during the winter surge was a definite no. While many people in our Urbana, Maryland, community have taken COVID-19 seriously, too many treat it like business as usual.

We recently tried to return Josh to sports, finally convincing him and ourselves that the benefits of playing baseball this spring on a team with one of his good friends would outweigh the risks. But Josh and one other child got turned away by a rec baseball league due to a registration mishap by the commissioner – and that happened too late for us to find another league, leaving us in limbo.

Josh badly needs to play sports again, as do so many children. Emotionally and socially, he needs to be around other kids. He needs to be physically active. He needs to be having fun. Instead, Josh feels dejected once again about organized team sports, and he’s even talking about “retiring” from playing in the future.

Youth sports dropouts were a problem even before the pandemic

If that sounds weird, it’s not. Even before the pandemic, the average child quit sports by age 11, most often because they stopped having fun, according to research by the Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative. During COVID-19, three out of 10 youth sports parents report their child is no longer interested in sports.

This should be a major red flag for the youth sports ecosystem.

As Project Play’s editorial director, I study these trends; as a father, I’m living through them with my son. My greatest fear? The youth sports model that I want for Josh – having fun, improving skills, competing without overemphasizing winning, playing with friends – will be unsustainable moving forward. And if that comes to pass, what will it mean for so many parents like me who view sports as a critical tool to help produce positive physical, social, emotional, and academic outcomes for our children?

The past year hasn’t just been hard on Josh. It has been tough on me as a parent and coach. I’ve seen how, as a society, we are not all in this together. We couldn’t agree on common criteria for how to open and reopen our states, businesses, and schools – much less youth sports, a fragmented quagmire that in normal times lacks national governance.

Without that leadership or common purpose, we’ve reached the point where a high school sports advocacy group and some parents have sued the state of Michigan, seeking to stop a new requirement that all teen athletes be tested weekly for the coronavirus in order to participate in practices and games. Even as vaccines, we hope, lead to greater inoculation against the virus, Michigan has emerged as one of the most troubling hot spots: As of early April, the state’s average daily infections were five times what they were in mid-February. New COVID-19 cases among children under 10 jumped 230 percent, more than any other age group. The second-highest increase was in the 10 to 19 age group, which saw cases rise 227 percent.

Physicians and infectious disease experts in Michigan told CBS News much of the rise in pediatric cases can be linked to the reopening of schools and youth sports. State data shows more than 40 percent of new outbreaks, defined as two or more cases linked by place and time, have come from either K-12 schools or youth programs.

Over the past year, other public health departments across the country have tied outbreaks to sports. Dr. Anthony Fauci and CDC Director Rochelle Walensky recently identified youth sports activities as a major driver of the virus spreading, more so than school classrooms. Infections aren’t necessarily happening due to on-field transmission. The bigger challenge is so many of the other activities associated with sports in which people can let their guards down: locker rooms, bench areas, transportation, team parties, and parking lot gatherings.

Many people absolutely are trying their best to safely return kids to sports. In some cases, they are succeeding. They should be commended. Other people are completely ignoring common sense. And that worries me. Despite those worries, I’ve questioned my own decision to keep Josh out of sports, wondering if my concerns were irrational. To get a better sense of what was actually happening, I attended some youth games in my community.

Too often, what I saw didn’t mirror the protocols communicated by leagues.

Parents and children alike are searching for answers

At a fall recreational soccer game featuring the team that Josh would have played, the coach wore a mask and made efforts to keep kids and parents distanced. The league even switched to seven instead of nine players on each side, partly to create more distancing but also because of declining participation numbers. On another field at the complex, however, there was a girls soccer game with parents packed tightly onto the sidelines. Almost all were maskless, disregarding dozens of signs stating that everyone must wear masks and stay six feet apart.

I attended several baseball games last fall at the league where Josh normally plays each spring. Nothing had changed. While baseball is theoretically a less-risky sport to play during a pandemic than many others, the safety promises made to me by the local commissioner in summer 2020 did not materialize when I watched. Most parents and coaches didn’t wear masks. Maskless kids interacted closely with one another on the bench. During every half inning, the teams gathered in a huddle for instructions and cheers. I recognized the same postgame huddle that Josh always loved – only this time, it was jarring to see maskless coaches recapping the game inches away from kids who eagerly waited to see who would be awarded the game ball.

Why would parents like me trust a league like this in the future? Why would we trust that society shares or even recognizes our concerns?

I sometimes feel alone with these thoughts. But, actually, they’re common. According to an Aspen Institute/Utah State University survey, 64 percent of youth sports parents said they worry their child will get sick by resuming sports when restrictions are lifted. In another Aspen Institute survey, two-thirds of high school students said they are very concerned or a little concerned about catching or transmitting COVID-19 through sports participation.

Those of us who have been silently reluctant to return our children to sports because we lack faith in those around us to follow common-sense protocols aren’t screaming loudly. We’re not grabbing headlines by staging return-to-play protests and filing lawsuits. But we may be a silent majority: According to a poll by The Washington Post and the University of Maryland taken in mid-March, 62 percent of parents whose kids played sports before the pandemic say their children are not currently playing organized sports.

What will youth sports look like when life returns to normal?

If and when those families return, they face more uncertainty. Earlier this year, it became painfully obvious to my wife and I that our son needed to play again. I did some homework, asking around about various local leagues’ protocols compared to what actually transpires during games. I talked with Josh until he felt comfortable with playing. I set a fairly low bar: Coaches should always wear masks and do their very best to keep kids distanced in the bench area and before and after games and practices.

Two days before a deadline, I registered Josh for a rec baseball league in Frederick County, Maryland, that seemed to meet my standards. We received the confirmation email. I was in touch several times with the commissioner. Josh was thrilled, since he would join a team that a friend played on and that would have me as an assistant. We bought a new bat, helmet, cleats, and batting gloves.

Nine days after registering, we were told that Josh no longer had a spot. The league thought it would have enough kids to field three or four teams. Instead, it had 28 kids for 24 spots. Two were still able to play by aging down to a younger level. Josh and one other child got left out since they registered last and had no flexibility with their age. After doing due diligence about COVID-19 – and still meeting the league deadline – we were shut out after initially being welcomed. How’s that for a message to parents?

The league left the decision up to volunteer parent coaches, who opposed 13-player rosters because of playing time challenges and complaints from parents if kids sit on the bench too much. While large roster sizes can certainly be challenging, many coaches, including myself, find ways to make them work. A good general rule for youth sports? Don’t turn away kids, especially those who need to play.

The commissioner was very apologetic and tried to form another team with a neighboring county. Not enough kids wanted to play. Parents across the country should be prepared to hear the same thing. The last time youth sports faced a similar crisis was during the Great Recession, when regular sports participation for kids ages 6-12 dropped from 45 percent in 2008 to 38 percent by 2014, according to the Sports & Fitness Industry Association.

That period led to youth sports becoming even more expensive and privatized, as wealthier parents fled to travel teams and many kids were left behind. Today, families face economic challenges and the challenge of parents feeling safe and kids retaining interest after a long layoff. We badly need more affordable, community-based youth leagues that parents can trust. But as we emerge from this pandemic, will we create and fund them? Or will we return to literal business as usual?

I don’t remember many specifics from the last game Josh played in February 2020, when I was co-coach of the Warriors, his rec basketball team. What I do remember was the postgame huddle in a hallway outside the gym: a despondent group of kids after a playoff loss, Josh consoling one of his teammates, and me and my co-coach trying to share some words of wisdom about overcoming challenges during the season. Then, like kids typically do, Josh and his teammates moved on from the dejection and switched to excitedly talking about plans for the team party.

Children are resilient – until they’re not.

I hope those joyful days of team sports will return for Josh and so many other kids. I’m no longer certain they will.

Monthly Issue

Now & Then: How Sport Has Transformed

For many, it’s been approximately a year in the life of a pandemic. We’ve seen tragedy, resilience, growing gaps of opportunity and opportunities for growth, juxtaposed in communities across the globe. The world of sport was not immune.

From a pause in play, to a push for more progressive racial justice, to unanswered questions about the long-lasting impacts of COVID-19 that still linger in the air - what do we wish we knew then, that we know now?