Athlete mothers pushing scientific, cultural change

Why this matters

As female athletes continue to have longer careers, there are also major changes in the strategies for postpartum recovery and the return to the game.

Mothers and athletes are both held in the highest esteem in our culture, yet mothers have never been classified, in the research field, as athletes. Recent research results may change that.

As we’ve seen most recently with Allyson Felix and Serena Williams, athletes are indeed mothers. It is a story that seems to be told and retold each time a star athlete returns to top-level competition soon after giving birth.

Most recently it was track star Felix when she won a 12th gold medal at the 2019 World Championships only 10 months after giving birth to her daughter via emergency c-section. Decades earlier, then record-holder Evelyn Ashford posed on the track for a 1985 New York Times feature with her new daughter, poised for what would be a triumphant return.

Before Williams shocked the world announcing that she’d won the 2017 Australian Open while pregnant, Evonne Goolagong’s pregnancy and post-motherhood Wimbledon win in 1974 were the big mother-related news of the tennis world.

What could make the motherhood story just one more mom at work? Perhaps a recent study could help bridge the gap.

These stories continue to earn popular applause along the way. They also create a social impact, contributing to strides in issues such as policy and salary talk. One such example was the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) shift to allow athletes to retain their earned seeding position in the event of injury, illness or pregnancy, a move “designed to fully support players in their return to competition, while maintaining the highest standards of athletic competition and fairness,” said WTA CEO and Chairman Steve Simon.

Then, there’s the catsuit.

Having suffered from serious, potentially life-threating blood clots, Williams chose a black bodysuit for her return to the French Open. The catsuit, while fun, was also functional, acting as compression stockings would, keeping the blood circulating and making clots less likely to form. The tights were a supplement to the blood thinners prescribed by her doctors as a result of the complications after the birth of her daughter.

Dedicated studies that specifically look at the post-pregnancy return to competition of elite athletes could help to eliminate stigma, enhance training and help to create a less-stressful return to the field of play. Researchers have already laid the groundwork, proving that pregnant women are in fact, endurance athletes.

The basic science behind the study released in June 2019 concludes that the ultimate physical limit of the human body is a threshold of 2.5 times the resting basal metabolic rate (BMR), the point at which the active body begins to break down its own tissue. To arrive at that figure, the team, led by Professor Herman Pontzer at Duke University, studied extreme athletes such as 3,000-mile ultramarathoners and Tour de France cyclists. Included in the study, in parallel to the athletes, was a group found to reach the near ultimate level — 2.2x BMR for a full 220 days, the length of a full-term human gestational period. That group was composed of pregnant women.

From the study:

“The increment of expenditure above 2.5× BMR (basal metabolic rate) cannot be met with additional intake and therefore cannot be sustained indefinitely. Notably, metabolic scope during human pregnancy (during which weight gain is imperative) and lactation peaks at ~2.2× BMR, which might constrain gestation length and fetal growth (24, 25).

Incorporating data from overfeeding studies, we find evidence for an alimentary energy supply limit in humans of ~2.5× BMR; greater expenditure requires drawing down the body’s energy stores.” Extreme events reveal an alimentary limit on sustained maximal human energy expenditure.

The findings sent waves through the science and sports communities. The synopsis leads to another question: what if one of the athletes studied were pregnant? A primary concern with the discussion of the research that extends from the separate and distinct studies is the suggestion that during pregnancy, women, by default, are not elite athletes. There has been, and continues to be, a dividing line separating the research on the physical implications of sport and pregnancy.

With growing urgency, it is imperative to study the impact of exercise and pregnancy on the elite athlete. In September 2015, the IOC held a meeting of 16 experts to address “exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes.” As a result of that meeting, the group produced five reports on specific target areas. The initial premise in Part 1 is key to what the sports industry sees happening now with better training, the long-term impact of Title IX and a growing interest in women’s sports:

“With an increasing number of elite female athletes competing well into their thirties, many may wish to become pregnant, and some also want to continue to compete after childbirth. … Increasing age is associated with decreasing fertility.” Exercise and Pregnancy, 2016 IOC, Part 1

The Return to Play

Dr. Michelle Mottola, an exercise physiologist at the University of Western Ontario, has decades of research, including studies and YouTube videos, outlining what happens to the body while exercising during pregnancy. Mottola was also one of the researchers assembled during the IOC group meeting in 2015. She posits that pregnancy may even increase a player’s performance level.

“With all the physiological changes that occur during pregnancy, it’s not like you can turn the valve off and switch back to normal once the baby’s born,” she told David Cox at The Guardian. “The postpartum period can potentially last up to a year afterwards. And, of course, everything depends on the woman, the birth, and her training regimen. But scientific evidence suggests that, in some ways, she may find performance a bit easier during this period because of the changes to her heart and her lungs.”

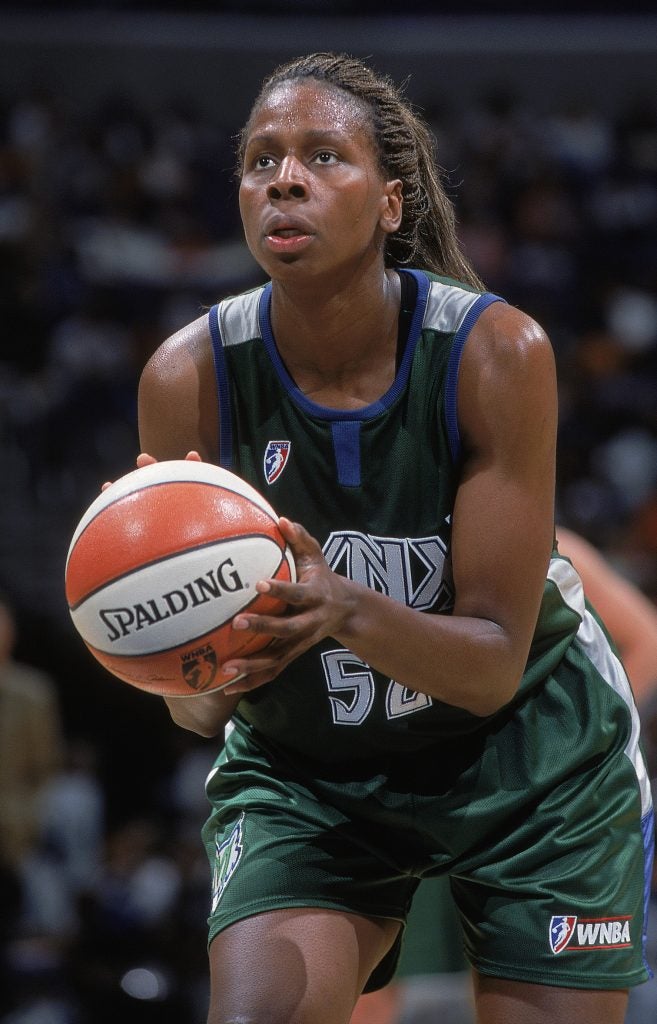

Women like Helen Darling and Val Whiting, former WNBA players, did choose to continue their playing careers post-pregnancy. They had an example, having seen Sheryl Swoopes return to the court after the inaugural season of the league. However, they still were concerned that their decisions to become mothers could derail their basketball careers, which they dearly loved. Their pregnancy stories differed, but both athletes were left to implement a training regimen in order to return to ultimate playing form while managing with postpartum issues.

The personal stories

Helen Darling, WNBA guard, 2000 - 2010

After her second year in the WNBA with the Cleveland Rockers and in the best physical shape of her career, Helen Darling found herself in an unplanned high-risk pregnancy with quadruplets. After being hospitalized, she delivered triplets at 34 weeks via cesarean section, having lost one fetus earlier. Her supportive coach at the time, lobbied for her, and the team signed her to a one-year contract, allowing her to keep half of her salary and continue to work out.

“I felt like I was starting over,” Darling said. “I remember going to train, breaking out in hives, my abs were weak. I felt limited. The trainers on the team and at Ohio State encouraged me to take it slow. Running was painful. My knees, my back — everything hurt.”

Though her mind was fully ready to compete, her body wasn’t ready. She worked with a minor league team in order to get back in shape. She was later traded. She didn’t feel that she’d returned fully competitive form until signing with the Minnesota Lynx in 2004, nearly two years after the babies were born. By the second half of that season, she’d worked her way back to the starting role with the new team.

“To play at that level requires a lot of toughness, and mental focus,” Darling said. “After you have the baby, that focus alters a bit.” She realized later that she was suffering from postpartum depression. “There’s the mental aspect of leaving the baby home when you’re back to work. There’s so much that goes into it. I had to work to pretend that everything is fine in public.”

She went on to regain her competitive form and have a great finish to her career, but feels that she couldn’t have done it without her supportive family, team and ultimately, the drive that led her to be a top athlete.

Val Whiting, WNBA power forward/center, 1997- 2002

“I took a sabbatical from the Detroit Shock in 2000-2001, and got pregnant during that time. It was unplanned,” Whiting said. “I had the baby March 2nd and training camp began in May. I opted to get induced a few weeks early in order to return to camp on time. I was into my career and didn’t want to lose my spot.”

At that time, she was the only mother on the Shock. Later, she was traded to the Minnesota Lynx. The coach at the Lynx at the time was also a parent, which was helpful.

“My personal expectations were way too high,” she said. “I didn’t realize what my body had actually gone through.” She journaled throughout the season, and looks back to see her depression chronicled on the page alongside how much she loved her son. She also learned later that the hormone relaxin still in her body eight weeks post birth made her more prone to injury.

She shone in training camp, earned a starting role and then her performance declined, along with player value. She returned the following year as a starter, but still struggled with confidence issues. After two seasons and recurring back issues, she retired and is uncertain if she would have worked harder to return had she not had a family.

“Going back to work as an athlete, trying to perform at a certain level, is different than returning to corporate America,” Whiting said. “We need a support group, some way for someone to tell us to ‘show yourself some grace.’ Something to handle the expectations we have of ourselves.”

Finding a standard workout after pregnancy

While leagues have adopted standard language for pay and maternity leave, there is no accepted physical training protocol to help players return to optimum competitive shape. Without exclusive research designed to create specific recommendations, it’s nearly impossible to create a workable program.

“But as evidenced by Williams, Brown (Sarah), Vollmer (Dana) and others, competing and training while pregnant is totally doable. Pregnancy isn’t a disability,’”Bill Moreau, the managing director of sports medicine for the U.S. Olympic Committee, told NBC in 2012. Still, we have a ways to go before a pregnant athlete excelling at her job will be commonplace rather than cause for excitement, questions or scrutiny.

After all, Vollmer and Brown, who both have their sights set on making the 2020 Olympic team in their sports, are just pursuing their careers.” Time.com

According to Mottola, creating a standard protocol will be difficult. “Pregnancy affects every system of the body; it’s unique. No other physiological process affects the entire body in the same way. Adaptations occur so that the baby is protected.

While exercise can be a part of a healthy pregnancy, but we don’t know where the upper threshold is, even for the elite athlete. That’s where the problem lies. Creating a standard protocol for any league or program is difficult because every pregnancy, every birth, and every baby is different. If there are issues, those issues can be compounded with high intensity training. It’s imperative that the athlete listens to their body and remains under the supervision of a doctor of midwife, or other medical professional for the duration of their pregnancy. Then, once the baby is born, does it sleep through the night? A new mother can be sleep deprived.”

Mottola also addressed the critical issue of mindset, which tends to be different in the elite athlete.

“It’s critical that the athlete not feel guilty, that they understand that the health of the fetus is most important. If they can’t run one day, it’s okay. An athlete is used to playing through pain. They typically will run through discomfort. They may have to adjust that. I can’t emphasize enough that focusing on the health of the fetus is vital.”

The IOC study noted that the age period of peak performance coincides with the predicted peak fertility years. If adequate funding and research are applied to studying the mother-athlete, it will be less of an either-or situation. To be fair, it is challenging to conduct studies on such a scant pool across the varied sports. Comparing tennis to swimming or track and field presents potential challenges.

Ten mothers represented Team USA in the 2016 Olympics, a number expected to increase in 2020, possibly reaching the 21 on the 2008 roster. A focused study on those athletes, combined with collegiate and pro top performers, would be enough of a baseline to begin to create a training protocol addressing the physical and mental issues mothers face in their return to form.

As more women choose to mother and compete, they’re sharing their stories on their own terms. Sydney Leroux’s recent Instagram post of breastfeeding in the locker room, dressed in uniform, garnered resounding applause. That could signal that popular culture is more than ready to embrace mothers to the field. It could also send a message to a generation of young girls that sports careers don’t have to stop at motherhood.

Still, there’s a long way to go. WNBA player Skylar Diggins-Smith made headlines announcing that she hid her pregnancy while playing out of fear of repercussions. There’s no way to know if her experience would be different if she, like Helen Darling, planned out a strategy to return to form, with the support of her coach. Regardless, the better the science and complete research, the less of a chance that the athlete’s return or pregnancy strategy is simply a league or coach’s decision. That’s better for everyone.

Mia M. Jackson is a writer based in Germantown, Md.